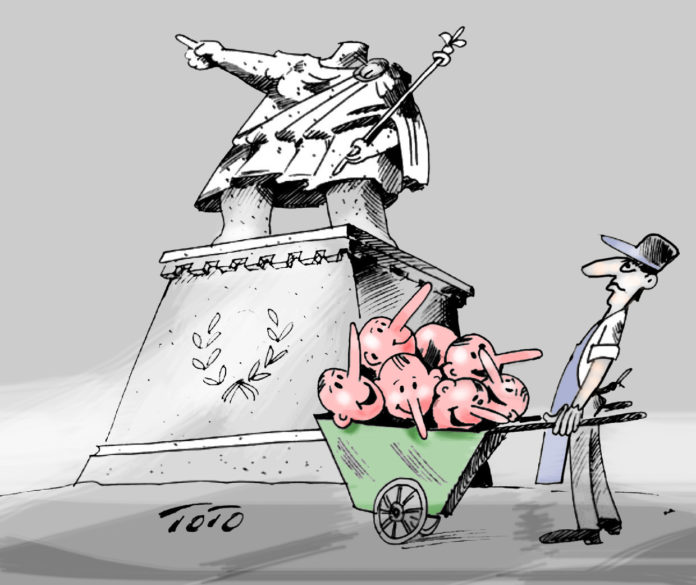

Armenia’s snap elections are scheduled to take place on June 20 and the constitution allows only 12 days of campaigning before that date. Howeever, the pre-election campaign has been shaping up for a long time and the opposition parties have been blaming Acting Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan for using government resources to conduct his campaign, particularly in rural areas, which seem to form Pashinyan’s power base.

The atmosphere is so tense that the animosities, anger and rancor charge the atmosphere to a degree in which civil and civilized political discourse has become impossible.

Even from the distant vantage point of the diaspora, objective analysis shows the election seems to be tainted by extreme polarization. One can seldom detect a rational political agenda in any camp, as all sides have been banking on and capitalizing on the failure — or presumed failure of — its opponent.

For example, the debacle of the 44-day war is one of the hot topics driving the political narrative. The opposition blames Pashinyan for the defeat while Pashinyan accuses the former regime of contributing to the defeat as a consequence of 30 years of inaction while Azerbaijan was in a race to build up and modernize its armed forces.

There are no calm voices in the middle to remind both sides that all administrations, including the current and former ones, bragged all along that Armenia has the most formidable fighting force in the region.

In addition, blame goes all around for Pashinyan’s humiliating loss of 75 percent of Karabakh, as well as the seven regions which were supposed to serve as a buffer or defense corridor for Karabakh. We have discovered that over the years negotiations with Azerbaijan had focused on the principle of swapping land for peace, after failing to force Baku to sign a treaty recognizing the independent status of Karabakh on May 12, 1994. Instead, at that time, a tenuous ceasefire was agreed upon, which turned into a political time bomb over the last three decades.

On May 10, 2021, in accordance with the constitution of the Republic of Armenia, the parliament tried and failed to elect a prime minister, which resulted in its dissolution, paving the way for snap elections.

During the last session of parliament, Pashinyan delivered a long and passionate speech defending the achievements of his administration.

“I regard what I just said as our biggest achievement: the citizens of the Republic of Armenia feel they are the masters of our country. At the end of the day, this is what the non-violent Velvet Revolution of 2018 was for and that goal has been achieved.”

The opposition may question this achievement but it is true that the 2018 elections represent the only instance — after Levon Ter-Petrosian’s first election — that corruption was uprooted and bribes did not in any way impact the outcome of the election.

That revolution also tried hard to eradicate red tape in government institutions, whereas in previous administrations, functionaries both high up and low-level performed their duties only after receiving bribes.

The Velvet Revolution also marked a generational turnover, bringing into power a young generation of legislators and administrators in Armenia, although that generation has revealed itself to be more hindered by inexperience than savvy with regard to innovation.

In his speech Pashinyan took credit for the rising of the level of Lake Sevan and the nine countries that have recognized the Genocide during his tenure.

This last assumption was disingenuous, as Pashinyan’s team, like Serzh Sargsyan’s, sent signals to the US administrations that the recognition of the Genocide was not a priority for Armenia, falling into the trap set by Turkey.

Pashinyan’s pledge in 2018 that the revolution will not indulge in vendettas against former officials was soon turned on its head as political lynching of the members of the previous administrations became a political sport to entertain the vengeful public. That public was also duped in two more instances, one domestic and one foreign.

In the first instance, Pashinyan’s administration promised to recover illegally acquired wealth, which gave hope to ordinary citizens that the program would place food on the family table, while all it did was to help chase the capital out of the country while failing to implement an economic program for the country.

In addition, Pashinyan came to power with a hidden anti-Russian plan, while claiming that the Velvet Revolution did not have a foreign policy agenda. Ironically, Pashinyan himself became a hostage to Moscow and today, Russia, holding Pashinyan in bondage, has the option of staying neutral in the parliamentary election because after the war Armenian politics themselves became a captive of Russian politics.

It is immaterial who is elected, as all the rulers are and will be at the mercy of the Russians.

Nikol Pashinyan weathered some potentially deadly political storms and now he feels reassured heading toward the parliamentary elections, especially as his opponents are not able to gain the attention of the voters. The 17-party coalition headed by former Prime Minister Vasken Manukyan, called Salvation of Homeland, once seemed poised for success, but fizzled and disintegrated quickly.

As well, President Armen Sarkissian called for Pashinyan to resign and the formation of a transitional government to be run by technocrats fell on deaf ears.

The government was also able to control rumblings in the armed forces headed by Gen. Onik Gasparyan.

Thus, battle tested, it is ready to face any other opposition on its way.

Pre-election polls, particularly in a country like Armenia, are hardly reliable and extremely biased. One of the few polls conducted are by International Republican Institute, which predicts Pashinyan’s My Step coalition will win with a margin of 33 percent. Second and third place, they predict, will be occupied by Prosperous Armenia headed by Gagik Tsarukyan and former President Robert Kocharyan, each by 3 percent. An alliance must cross the bar of 8 percent to be elected.

At this time, two major visible forces are facing each other: Pashinyan and Kocharyan.

Kocharyan’s coalition has made a lot of political waves but it is very difficult to predict where it is heading.

Kocharyan’s recent political rally in Yerevan brought to Liberty Square 30,000 people, which indicates that his movement is gaining momentum. His alliance, Armenia Bloc, includes the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) and the Syunik-based Reviving Armenia party, headed by the former governor of that province, Vahe Hagopyan.

His association with the ARF is a double-edged sword. While the latter is the only political party in Armenia with a history and political platform, its political principles are overshadowed by its past association with an unpopular regime, where it has also been in public perception as a prime candidate for the gravy train. The ARF is also the best organized party, which can help Kocharyan’s camp practically, yet may prove to be a drag on his popularity.

The other enigma is the association of the Syunik forces with Kocharyan. That region has been Armenia’s Achilles heel where Pashinyan was even banned from visiting, setting a

continued on next page

from precious page

dangerous precedent for a duly-elected prime minister who should extend his constitutional power over the entire country.

The region is also in the crosshairs of Azerbaijan. The more domestic problems are fomented in that region, the more tenuous the region’s destiny becomes. On top of all those problems, Sergey Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister, recently visited Armenia, and suggested that Armenia and Russia sign a separate agreement, supposedly intended to protect that region. This would give a free hand to Moscow to bargain away Syunik with Turkey and Azerbaijan against any practical gains for Russia.

Another side show which involved Kocharyan was President Levon Ter-Petrosian’s initiative. Indeed the former president met with all the former presidents of Armenia and Karabakh to form a coalition. Ter-Petrosian’s purpose was to stop Pashinyan — his former protégé — saying the latter’s return to power would be disastrous for Armenia.

Ter-Petrosian is known for his vitriolic characterizations, which has not changed, as he stated that Pashinyan’s continuing rule will be more dangerous than any threat that may come from Azerbaijan and Turkey. There are no takers for the Ter-Petrosian proposal.

Prosperous Armenia, which had the largest faction after My Step in the parliament, will participate alone. The Republican Party of Serzh Sargsyan will be headed by Armen Ashodyan and is forming an alliance with Arthur Vanetzyan’s Homeland Party. Vanetzyan was the former head of the security forces in Armenia. Ter-Petrosian’s Armenian Congress has yet to find a platform after failing to convince the two former presidents.

Russian behavior and duplicity in the recent war has pr ovided wind for the sail of pro-Western forces. Thus, there are three parties that openly side with the West: National Popular Axis, composed of Sasna Tserer and the European Party of Tigran Khezmalyan. The other parties are called In the Name of the Republic, headed by Arman Babajanyan, and Christian Democratic Party, led by Levon Shirinyan. These parties have vehemently anti-Russian platforms.

There are also many fringe groups looking for partners. The situation is still fluid; new coalitions may yet be formed or other parties may disappear from the radar.

There is a general apathy towards the elections because the citizens are tired of unsubstantiated pledges and the polarization ripping society apart. According to the abovementioned polls, 44 percent of the population does not support any party and 45 percent is unhappy with the political direction of the parties.

The question on everyone’s mind is will the elections prove to be a blessing in disguise or an amplification of the current catastrophe?