We have already seen that the Armenian draftees from the eastern provinces, whom we clearly distinguished from those native to other vilayets, were assigned to both combat and transport units in the first months of the war. We must now say something about the treatment reserved for them after the deportations and massacres began in the Erzerum region.

Let us start by pointing out that their fate was in the hands of the commander-in-chief of the Third Army, Mahmud Kâmil, as was that of the civilian population, inasmuch as the government had officially left it up to the army to decide how “urgent” the “displacement” of the “suspect” populations from the war zones to “the interior” was.

Yet it was largely on the Armenian population that the Ottoman troops stationed in the vilayet of Erzerum depended for their maintenance; the Armenians billeted them in their own villages – the lack of barracks was no secret from anyone – fed them, provided them with draft animals, transported supplies for them on its backs, gave them medical care, and furnished them with products turned out by its craftsmen. In “displacing” the Armenian population “to the interior” – that is, in cutting off this source of logistical support – Mahmud Kâmil risked making the position of the Third Army untenable in very short order, as the vali of Erzerum, Tahsin, pointed out. In other words, from a strictly military point of view, the elimination of the Armenian civilians could be regarded as sheer folly.

From a political and ideological point of view, on the other hand, it was perfectly consistent with the objectives of the Young Turk Central Committee, which sought to exclude non-Turks from the eastern provinces. Can we, moreover, imagine even for a moment that the handling of the Armenian question was really entrusted to Mahmud Kâmil or the army?

This was impossible in a system in which the party’s Central Committee reviewed all decisions. We must rather assume that the “security of the army’s rear base” was merely an alibi designed to legitimize the extermination policy by providing it with a legal facade – the more so as the political decisions made in Istanbul clashed with the immediate interests of the military.

That said, we must ask who controlled the fate of the tens of thousands of Armenian conscripts who had been plucked from their natural environment and separated from their families. The examples at our disposal indicate that the army maintained its right to revise decisions bearing on these soldiers at least until May 1915, although we saw that, from winter 1914–15 on, the treatment meted out to them bordered on a policy of elimination by exhaustion or, for the less docile, incitation to desertion.

During the deportations, the authorities sometimes even considered not deporting soldiers’ families, although this held only for recruits from the provinces of western Anatolia, who fought in the Dardenelles or on the Syrian-Palestinian front. None of the contemporaneous accounts we have suggest that similar measures were ever considered in the eastern vilayets. It was as if the fate of the populations living in the Armenians’ homeland had been clearly dissociated from that of the groups scattered throughout the west.

We have already seen that, from late February on, draftees in combat units who were natives of the vilayets of Erzerum and Bitlis were executed in small groups.

However, the fate of these groups of combatants, who represented a minority of the Armenian draftees, has to be distinguished from that of the soldiers serving in the amele taburis or labor battalions. It would seem that the doom of the latter was sealed when that of the civilian populations was.

Thus, the decision to liquidate them in the area under the jurisdiction of the Third Army was made around 15 May. The most frequently used method consisted in turning them over in groups of 200 to 300 to çetes, who saw to their execution in the killing fields that we have already mentioned. This held, for example, for the 200 conscripts from Hınis massacred in Çan, near Kıği, as well as the 4,000 worker-soldiers from Harput who had been put to work

on the road between Hoşmat and Palu; a deportee fleeing for his life saw their corpses, still in an early stage of decomposition, as he was making his way toward Dersim.

There were also intermediate cases, such as that of the drafted artisans employed directly by the army or in military workshops; the treatment of these people was less systematic. Thus, 60-yearold Eghia Torosian of Mamahatun, drafted despite his age, worked first in the hospital in Erzincan and was then, in May 1915, assigned to the 800-man-strong 35th Labor Battalion.

These workers were employed in a military firm located 20 minutes from the center of the town of Mamahatun. Despite the critical demand for experienced craftsmen, even this battalion was gradually shorn of a majority of its members, who were taken beyond the city limits at night in groups of 15 to 20 and quietly executed by çetes of the Special Organization.

Nonetheless, 235 artisans survived.

We also know about the case of Rupen Toroyan, a draftee from Erzerum. Along with his Muslim comrades, Toroyan was responsible for transporting supplies from Erzerum to the front. He witnessed the looting of the Armenian villages of Pasın, the sacking of the church in Olti, recently occupied by the Ottoman army, and the mistreatment of the 200 Armenians taken hostage in Olti.

In Odzni, where his regiment was based, he saw how Armenian villagers were expelled so that their homes could be taken over and their food stocks plundered. In the nearby village of Ilija, he witnessed the expulsion of the inhabitants by gendarmes as well as the suffering these homeless peasants endured outside the village for six days before all of them were executed a short distance away.

One of his Turkish companions, Corporal Ibrahim, confirmed what Toroyan had seen when he complained that he had had nothing of the windfall associated with the massacre of these Armenians, who were carrying a great deal of gold, “especially the women.”

After his return to Erzerum, Toroyan witnessed the departure of the convoys of deportees. Until then, he had not been molested in any way. His corporal nevertheless offered to save him if Toroyan brought him “a pretty girl.” Arrested, like all the other Armenian draftees, he was sent off in a convoy comprising around 1,000 people, guarded by 60 gendarmes.

The following morning, near Aşkale, çetes and soldiers encircled the caravan, stripped the deportees of their belongings and transferred the 200 to 300 conscripts in the convoy to the prison in Aşkale. Four or five of them starved to death every day.

A few days afterwards, the conscripts from Erzerum – a detail in Toroyan’s account indicating that there were other soldiers in the prison – were sent to work on the roads. They joined other Armenian workers under the surveillance of soldiers: one soldier for every ten recruits. Toroyan notes that he worked under these conditions for a period of five months, during which many of the Armenians, including his brother, were so badly mistreated that they died.

The authorities then separated out craftsmen like Toroyan and sent the others “to the slaughterhouse of Kemah Deresi.”

The remaining 200 men, who continued to work under appalling conditions, offered to convert to Islam. The question, says Toroyan, was referred up the hierarchical ladder until it reached the vali. Two days later, the men received a favorable response and a mullah arrived to initiate them into their new faith. Three months later came an order to assemble all the Armenian converts of Aşkale and send them to Erzerum.

With seven of his companions, Toroyan worked in the state ironworks in Erzerum for some time. Ultimately, however, all of them were taken to a gorge near Aşkale, where hundreds of conscripts were shot on 15 February 1916. Toroyan, along with one of his comrades from Bitlis, escaped with his life because he had hidden under the corpses of his companions.

He succeeded in finding refuge with a Turk from Aşkale who told him: “From now on, you’re going to protect me: the Russians are coming.” There is every reason to believe that the sudden advance of the Russian army sealed the doom of the Armenian recruits still employed by the local authorities: they were liquidated despite their conversion to Islam.

There are a number of rather interesting stories of survival among the conscripts.

The story of Krikor Keshishian from Pakarij is an example. When the general mobilization was announced, Keshishian was in prison. Although he was released in November, his status as a former convict meant that he could not legally serve in the army. He was mobilized nonetheless and sent to Mamahatun, where he joined the recruits assigned to transport military supplies to the front on their backs. Of a pragmatic turn of mind, Keshishian thought that it was ridiculous to impose an ordeal of that kind on soldiers, and bought three mules that could be used to transport supplies. The military authorities did not appreciate this display of initiative: they confiscated Keshishian’s mules and he deserted. His parents then asked him to turn himself in, knowing that if he did not their house would be demolished.

On 24 January 1915, the Keshishian family home was burned down with all the occupants inside, except for the men, who fled. According to Keshishian, 366 people from the villages of Tercan who had paid the bedel to avoid military service were arrested as deserters and sent to Erzerum on 15 February.

Thus, it would seem that the commanders of the Third Army collaborated with the Special Organization, which was apparently responsible for executing the orders to eliminate the Armenian conscripts in the amele taburis.

In certain instances, however, the military was able to retain a minimal number of craftsmen to ensure that its logistical needs would be met.

We do not have much material on the transmission of deportation-related orders in the area under the Third Army’s jurisdiction. However, it seems that, at least until mid-summer, the commander-in-chief of the Third Army, Mahmud Kâmil, sent many cables ordering that Armenians be exterminated, as was later admitted by General Süleyman Faik Pasha, commander of the garrison in Mamuret ul-Aziz.

Yet, beginning on 8 August 1915, the military authorities received orders no longer to concern themselves with the deportations but simply to cooperate with local government officials. It is likely that this decision was reached after an 18/31 July 1915 meeting in Erzincan attended by the valis of Erzerum, Trebizond, Harput, and Sıvas, as well as many mutesarifs and kaymakams, such as the kaymakam of Bayburt.

This meeting was without a doubt chaired by Bahaeddin Şakir. We do not, of course, know the substance of the discussion that took place in the fief of Şakir’s main collaborator, in the sancak where most of the massacres of the vilayet’s Armenians were carried out.

However, given the date of the meeting, there is every reason to assume that it was called in order to draw up a preliminary balance sheet of the eradication of the Armenian population in the eastern provinces and, probably, assign the civilian authorities the task of completing the project conceived by the Ittihadist Central Committee.

More particularly, the aim was to mop up the last Armenians who had somehow managed to elude the machine that Istanbul had put in place.

The circular telegram that the commander of the Third Army, Mahmud Kâmil, sent from his headquarters in Tortum on 10 July 1915 to the valis of Sıvas, Trebizond, Van, Mamuret ul-Aziz, Dyarbekir, and Bitlis is the only official document on the question that we have.

Submitted to the court-martial at the session of 27 April 1919, it is of inestimable value, for it provides proof of the Ittihadists’ determination to pursue their project of destruction until they had eliminated the last Armenians left alive, even those who had converted to Islam or “integrated” into Turkish or Kurdish families:

We have learned that, in certain villages the population of which has been sent to the interior, certain [elements] of the Muslim population have given Armenians shelter in their homes. Since this is a violation of government orders, heads of households who shelter or protect Armenians are to be executed in front of their houses and it is imperative that their houses be burned down. This order shall be transmitted in appropriate fashion and communicated to whom it may concern. See to it that no as yet undeported Armenian remains behind and inform us of the action you have taken. Converted Armenians must also be sent away. If those who attempt to protect Armenians or maintain friendly relations with them are members of the military, their ties with the army must be immediately severed, after their superiors have been duly informed, and they must be prosecuted. If they are civilians, they must be dismissed from their posts and tried before a court-martial. The Commander of the Third Army, Mahmud Kâmil, 10 July 1915.

This telegram bears a revealing annotation, dated 12 July and probably made by the vali or a high-ranking official of the vilayet of Sıvas: it requested that the order be transmitted “secretly, and in writing only in exceptional cases.”

The content of this circular leaves little room for doubt about the intentions of the commander of the Third Army, who probably did no more than carry out orders received from Istanbul to apprehend the last Armenians who had eluded the deportations by conversion to Islam, flight, or some other expedient. The severity of the punishment risked by Muslim families who were tempted to protect Armenians is a measure of the Ittihadist regime’s determination to eliminate the entire Armenian population without exception.

Revelatory in this regard is the case of two Armenians who were close to the German vice-consul of Erzerum – Sarkis Solighian, the owner of the building in which the consulate was housed, and Elfasian, the former dragoman. The vice-consul, Scheubner-Richter, was harassed for weeks by Hulusi Bey, the Erzerum police chief, who demanded that these two protégés of the consul’s be deported without delay. They were finally arrested on 1 July 1915.

Scheubner-Richter’s appeals to Vali Tahsin notwithstanding, he proved unable to save the two Armenians, who, as everyone knew, were his only independent source of information about events in the region. As Hilmar Kaiser points out, the authorities’ behavior was meant to demonstrate to local public opinion that even the German vice-consulate was incapable of protecting anyone.

It is clear that the steps taken by the civilian and military authorities around mid-July 1915 were designed to carry the deportations to their term, eliminating the last Armenians in the vilayet. Witness two circular telegrams sent on 20 July by the interior minister to the local authorities, including those in Erzerum. They requested a precise assessment of the demographic situation in these regions before and after the deportations, as well as information on the number of Armenians who had converted to Islam and local government officials’ attitude toward them. The aim, no doubt, was to evaluate the results of the work already accomplished, the better to decide on new measures.

To be continued

Note- this chapter is from Raymond Kévorkian’s book ARMENIAN GENOCIDE: A Complete History, pp. 311-315.

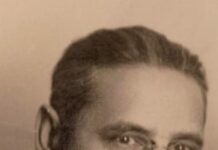

In picture- Levon (surname is unknown), Armenian soldier of the Ottoman army, 21 October 1917 – http://www.genocide-museum.am/eng/online_exhibition_8.php