After occupying Kars, the Turkish armies moved towards Alexandrapol. On November 3, Ohanjanyan proposed a ceasefire to Karabekir, but the Turks delayed and entered deeper into Armenian territory.

On November 5, the commander of General Silikyan’s army reported to Nazarbekyan, “The military units are leaving the front arbitrarily. The soldiers are deserting in groups and not obeying the commanders.”

When the Turkish army was approaching Alexandrapol, the Bolshevik committee met them with a red flag. The first words of the Bolshevik representative were, “Welcome to the liberating Turkish army, which has come to free us from this Dashnak hell.”

On November 5, Ohanjanian telegraphed the allied governments and US President Wilson that Armenia had been crushed in the struggle against the common foe. Armenia “sends a last appeal and begs actual relief by intervention in the armed conflict and by causing the enemy to cease military operations through diplomatic channels.” In Tiflis, Tigran Bekzadyan called at every allied mission to deplore the abandonment of Armenia despite its fidelity to the allied cause. American Consul-General Charles Moser regretted the difficult situation in which the Armenian people and government found themselves, but he reminded Bekzadyan that the United States was not a signatory to the Treaty of Sèvres. The American government had recognised the independence of Armenia and had helped as much as possible, but it had never assumed any commitment to defend the republic.

Minister of War Ter-Minasyan sent a coded telegram to Prime Minister Ohanjanyan in which he stated, “Our forces don’t want to fight; they want peace. I propose starting negotiations and signing a peace treaty. If the war continues, we will lose everything.”

A week before the capture of Kars, on October 23, the Ankara government had published an announcement about the battles between “the Milli forces and the Dashnak marauding groups in the Caucasus,” in which it said that, “Armenia aims at eliminating or forcing the migration of Turks settled in the country. These make up half the total population. By the end of 1919, 199 Turkish villages in the regions of Armenia alone have been burned, and a large part of their population of 135 thousand has been annihilated. On September 24, our frontline positions faced an attack and, after defeating the enemy, they pursued them to Sarighamish. The aim of the Armenian attack was the capture of Erzurum. Pursuing the Armenian raiding groups who butcher our brothers over the border is our nation’s vital right and legitimate defence.”

On November 6, 1920 Karabekir proposed the terms of the ceasefire: hand over Alexandrapol’s fortress and railway station. However, when the Armenian side satisfied the severe Turkish terms, on November 8, they presented new, even stricter terms.

On November 10, military operations resumed in the direction of Igdir where, in the previous weeks, the Armenian forces led by Dro had fought against the Turks.

On November 11, Chicherin wrote to Kemal, demanding that the attack on Armenia by Turkish forces be halted. However, that same day, the war resumed in several places. The Turks attacked the units in Jajur. The Armenians retreated back to Hamamlu (Spitak). Heated battles also took place in Aghin. These were the last military operations. An Armenian-Turkish neutral zone was declared from the station at Nalband to Gharakilisa. However, in reality, the Turks were looting there, as they were in the other Armenian regions they had captured.

At the same time they were negotiating with the Turks, the Armenian leadership petitioned Moscow, appealing for their mediation with regards to reconciliation with the Turks. The Foreign Affairs Commissar Chicherin designated Budu Mdivani, who had been the Russian Ambassador to Ankara since October 1920, as mediator in the Armenian-Turkish negotiations.

The Bolshevik and Kemalist plan to divide Armenia between themselves is also confirmed by the minutes of the November 19 meeting between Prime Minister Ohanjanyan and WarMinister Ter-Minasyan on the one hand, and Legran and Mdivani on the other. Legran considered the concession of Kars to the Kemalists to be the pre-condition for Russian mediation. “Would the Armenian government agree to concede Kars to the Turks? I consider this issue to be fundamental. If Armenia agrees, the issue of the future strengthening of your front and requests for Russian military assistance would be eliminated, because the Turks will sign the peace treaty with Armenia.”

The Bolsheviks made it almost patently clear that their aim was to bring Russian forces into Armenia, supposedly to restrain the Kemalists. Legran says, “The Turks are extremely realist politicians, and if their armed forces are not opposed by an evident military threat, then it is difficult to expect any positive results from mere diplomatic speeches.”

Ter-Minasyan reminded Legran, “Once, we paid for our orientation towards the north with the lives of millions of our people. The help of the Russian army came late. Why should we not assume the possibility of the same happening this time?” The Kemalists were also demanding the concession of Vorontsovka (Tashir) as part of the ceasefire. Ter-Minasyan, finding this behaviour by the Kemalists to be incomprehensible, said to the Russian representatives that presumably “the Turks are a tool in the hands of some outside power or other.” Other than that, “Why should Russia start a war against the Turks, a war which might arm all the Muslims of the region against it? A notion has been formed in the minds of our army and nation that Turkey is working together with Russia.”

Mdivani replied, “The conclusions of the war minister are not correct. The reason is not that a notion has been formed in the minds of the army and nation that Soviet Russia in this case is working with the Kemalists. The reason goes much deeper. The Entente does not wish, and is powerless, to help Armenia. The people are searching for a way out of the created situation. They are looking for external support. That support can only be Russia. It is time to understand and accept sovietisation, which will save Armenia and the final destruction of the Armenian nation.”

Soviet rule was declared on November 17 in occupied Alexandrapol. A revolutionary committee was created. Rushti Pasha was appointed Kemalist representative. By proclaiming Soviet rule in the region of Alexandrapol, the Turks tried to make the Revkom accessories to their criminal deeds.

It was only on November 18, when Karabekir was already in Alexandrapol, that the Armenian side managed to sign a humiliating ceasefire. On November 23, Armenia’s bureau-government left for Alexandrapol in order to begin negotiations with the Turks. The delegation was headed by Khatisyan who, with Yerevan’s knowledge, was instructed to renounce the Treaty of Sèvres. Ironically, while blood-soaked Armenia was being torn apart by the Turks and Russians, US President Woodrow Wilson, on November 22, 1920, presented his proposed map of a new Armenia, encompassing 160,000 square kilometres of territory. The Armenian delegation learnt about this draft during the Alexandrapol negotiations.

After the meeting between Prime Minister Ohanjanyan, War Minister Ter-Minasyan, Legran, and Mdivani, the Bolshevik-Kemalist agreement to divide Armenia between themselves and sovietise it became finally obvious. The bureau-government resigned on November 23.

On November 23, the editorial in Haraj entitled “Towards Reconciliation” read, “We, who have continually tried to create a Greater Armenia by putting our faith in the strength of outsiders, have been convinced of how deceptive and dangerous those hopes were after this stunning defeat. If we had been real politicians and had accepted in good time that it is not right to be led by national political aims while leaning not on our power, but that of others, and if we had been able to correctly measure our own strengths and the true weight of our abilities, we should never have strived to create a Greater Armenia. We should strive in all sincerity and determination to eliminate all obstacles that to date make Armenian-Turkish friendship impossible.”

The editorial entitled “The Issue of Reconciliation and Our Orientation” in the November 24 issue of Haraj emphasised the importance of coming to terms with Turkey. “If the Armenian nation wishes to live and secure its permanent physical existence and that of its state, it must not have Russian, but Turkish orientation. If the Armenian people had not had Russian orientation during the recent pan-European war, but had been with Turkey, most probably it would have avoided the massacres. We must understand that it is not by leaning on outsiders that we can achieve peace, but that only by relying on our own strengths will we decide our fate with our strong neighbours, the Turks.”

A new government was formed on November 24, headed by Simon Vratsyan. On the same day, a government proclamation was published signed by Vratsyan: “Armenia’s state structure will be anchored not on the empty and dangerous encouragement of foreigners, but on Armenia’s true abilities. Our operational motto will be sincere reconciliation with Turkey and harmony and peaceful existence with all our neighbours.”

Vratsyan also appealedto Mustafa Kemal with willingness to establish new relations with Turkey. This is known through Kemal’s letter of response, dated November 29:“I received your telegram in which you declare that you wish to have friendly relations with your neighbouring states with satisfaction and see that the negotiations begun in Alexandrapol will result in securing the mutual interests of the two sides.”

The ARF had ordered Khatisyan to sign a treaty with the Turks. On November 27, during the second session of negotiations and with the approval of SimonVratsyan, Armenia’s last prime minister, the Armenian delegation renounced the Treaty of Sèvres. At eight o’clock in the evening, the fourth and last session of the conference took place. The Armenian delegation announced that it accepted the treaty. The reading of the treaty followed, article by article. “We managed to include some minor amendments toour benefit: for example, including a part of Aghbaba within Armenia’s borders and increasing the number of forces from 1200 to 1500,” wrote Khatisyan. “We had long debates around Ani [medieval capital city, the imposing ruins of which lay on the western bank of the Akhurian River], Nakhijevan, and Surmalu, but the Turks made no compromises.”

In the early hours of December 1, a consultation took place with the participation of the ARF Bureau, the Central Committee, the ARF parliamentary faction, members of the government, and several well-known officials. The answer to Legran’s ultimatum had to be given during the consultation. Dro announced that he did not have an army to fight against the Bolsheviks; the Armenian soldier would not open fire on Russians.

On December 1, Vratsyan informed Khatisyan that the severe terms that the Kemalists presented have strengthened the Soviet positions. They have already captured Dilijan and are moving towards Yerevan under the banner of rescuing Armenia from the Turks. The Armenian forces in Dilijan have welcomed the Bolsheviks. The prime minister announced that, under such circumstances, the government agreed to the sovietisation of the republic, on the condition that it keeps its independence.

Days earlier, on November 22, Armenia’s Revkomhad been organised in Baku. The six-member Revkom included Sargis Kasyan (Ter-Kasparyan) as chairman, Askanaz Mravyan, Sahak Ter-Gabrielyan, Alexandre Bekzadyan, Isahak Dovlatyan, and Avis Nurijanyan.

Several days later, Kasyan and Nurijanyan departed for Kazakh. Thus, the Revkom moved from Azerbaijan to Armenia and established a Soviet regime in Ijevan.

On December 2, 1920 the agreement for the sovietisation of Armenia was signed by Dro and Terteryan on the one side, and Legran on the other. Armenia was declared an independent Soviet republic with the province of Yerevan and all its districts, a part of the province of Kars, the district of Zangezur in the province of Gandzak, a part of the district of Kazakh, and those parts of the province of Tiflis that had been under Armenian control up to September 28, 1920 within its territory.

During the days of sovietisation of Armenia, Turkish-Armenian negotiations continued in Alexandrapol. From Dilijan, Kasyan conveyed the news of the sovietisation of Armenia to Karabekir. Vratsyan in turn sent a telegram to the Armenian delegation, informing them of the government’s resignation, making them understand that they must accept the Turkish terms and sign the treaty of Alexandrapol.

In the early hours of December 3, when Soviet rule had already been forced on Armenia, the Armenian-Turkish treaty was signed in Alexandrapol.

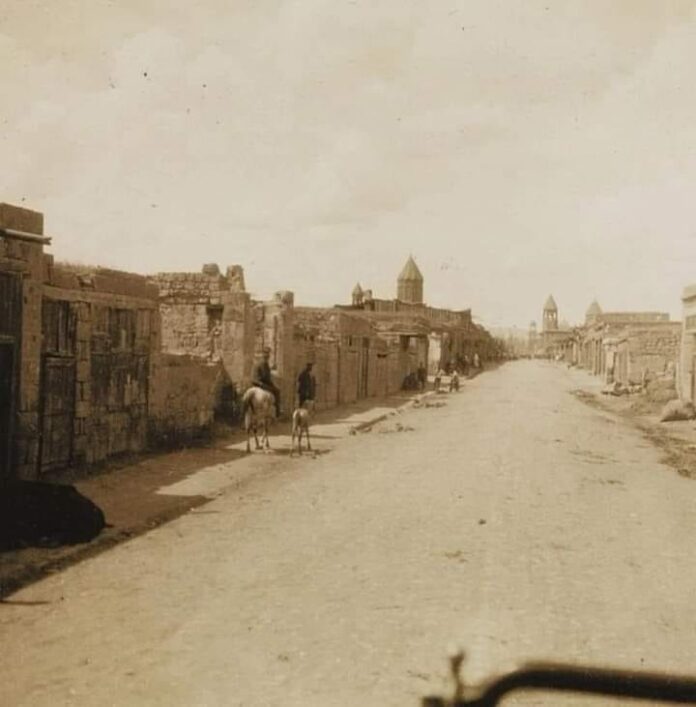

The Turks stayed in Alexandrapol until April 21, 1921, during which time they ransacked the area and massacred its starving people. Before leaving, the Turks rounded up thousands of Armenians from the villages in the Alexandrapol region and drove them to the Massacre or Herher gorge, close to Jajur, and mercilessly butchered them there.

Soviet rule was accepted in Armenia almost without any resistance, with the exception of Zangezur, where Garegin Njdeh continued to struggle for several months against the invading Red Army and maintained partial Armenian independence.

On December 2, 1920, Legran arrived at the Armenian foreign ministry, where Dro and Terteryan were waiting. In consultation with Vratsyan, the sides accepted a formula whereby, pending the arrival of the Revkom, the entire administration would be entrusted to Dro, who was named commander of the military forces of Soviet Armenia, assisted by Otto Silin, a member of Legran’s mission. The agreement signed, Terteryan and Social Revolutionary leader Arsham Khondkaryan drafted the final act of the Armenian government: “In view of the situation created in the land by external factors, the Government of the Republic of Armenia in its session of 1920 December 2 decided to resign from power and to transfer the entire military and civil authority to the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, to which position is appointed Minister of War Dro.”

According to the agreement, the commanders of the Armenian army were not to be held to account. Five of the military revolutionary committee members were appointed from the communist party: Kasyan, Mravyan, Ter-Gabrielyan, Bekzadyan, and Nurijanyan, and two from the leftist Dashnaks, Dro and Terteryan.

By five o’clock in the afternoon, Vratsyan and his ministers had closed their offices and left the government building. Vratsyan later recalled: “We quietly dispersed to our homes. Quiet and calm was the city as well. Quiet also was Masis [Mount Ararat], wrapped in thick clouds, musing over the vanity of the world. This, alas, is what the Bolsheviks subsequently acclaimed as the ‘bloody coup’ of the workers and peasants. That evening, Father Abraham [Avetik Sahakyan] and Papasha [Levon Tadevosyan] came over, sad, in an uncharacteristic manner. They sat without speaking. I, too, was silent, near my desk. On my left side, observing us from the wall was the painting that the artist Yerkanyan had gifted, the sharp-eyed, pretty-headed, and buxom girl of Trebizond. From the broad window, the silhouette of Masis could be made out in the twilight. Silence enveloped the room, as it did our souls.”

December 2 had not left a significant effect on the public. In Vratsyan’s words, “Only the Turkish-Armenians, who were grieving the destruction of independence, were extremely sad. Because of communication difficulties, the majority of the districts were surprised, but there again did not seem to be any particular regret. Some were even happy, saying, ‘Finally the Russians will come and save us. We will be safe from the Turks, we will have bread, we will also have fuel, and life will become easier’. This was the general feeling.”

A segment of Armenia’s former ministers and members of parliament fled Armenia on December 2 and began moving towards Georgia through the mountains. They were arrested on their way and brought back to Yerevan, where they remained imprisoned. “Others moved towards Zangezur. Of the former ARF member ministers, Vratsyan, Kajaznuni, Khatisyan, Tigranyan, and Gyulkhandanyan were living in freedom,” Khatisyan wrote. “Some of the ARF members of parliament proclaimed that they had left the ARF and tried to form a group, but they did not succeed. Some of them joined the Communist Party and the rest fled Armenia two or three months later.”

News of Armenia’s sovietisation was received with fanfare and celebrations in Azerbaijan. Narimanov announced the victory of Soviet order in Armenia and read the declaration of the Azerbaijani Revkom at a plenary meeting of the Baku Soviet. The declaration composed and approved that day read: “Soviet Azerbaijan… declares that henceforth no territorial question can be the cause for mutual blood-letting of two, centuries-long neighbouring peoples, Armenians and Muslims. The toiling peasantry of Nagorno Karabakh is granted the right to self-determination, and all military activities must cease within the bounds of Zangezur, from which the troops of Soviet Azerbaijan are withdrawing.”

A second decree reportedly signed on November 30 by Azerbaijani Revkom chairman Narimanov and Foreign Affairs Commissar Mirza Davud Huseinov made the ceding of the disputed territories to Armenia even more explicit: “From today, the disputes about the boundaries between Armenia and Azerbaijan are declared as over. Nagorno Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhijevan have to be considered a part of the Armenian Socialist Republic.”

During a special gathering of the Baku Soviet, the Azerbaijani Revkom, and prominent Bolshevik comrades in the state theatre on December 1, Narimanov saluted the liberation of Armenia and read the decisions adopted by the Revkom the previous day. In a historic address, Sergo Orjonikidze responded to Narimanov’s declaration by exclaiming that only Soviet order was capable of lifting the burden of inter-ethnic enmity: “Comrade Narimanov’s speech is very definite. He read us his declaration. The names of Zangezur, Nakhijevan, and Karabakh, the content of those words means absolutely nothing to the ears of an unfamiliar Russian person. Some Zangezur with barren mountains, neither bread nor water. Some Nakhijevan, swamps, malaria, and nothing else. Some Nagorno-Karabakh, what is there in Karabakh? Nothing. And so, Comrade Narimanov says, ‘Take those for yourselves. Take those infertile lands for Armenia’. It would seem as if Soviet Azerbaijan is being freed from an added burden. But no! In those districts, on those infertile lands, the crux of the so-called Armenian-Muslim question exists… That act which was read here is an act of the greatest importance. This is a historic act, which has no equal in the history of humanity.”

On December 4, a new Armenian government, presided by Sargis Kasyan, head of the Revkom, arrived in Yerevan. On the same day, in an article entitled “Long Live Soviet Armenia”, Stalin wrote, “On December 1, Soviet Azerbaijan withdrew from the disputed regions and announced the transfer of Zangezur, Nakhijevan, and Karabakh to Soviet Armenia.”

From Tatul Hakobyan’s book ARMENIANS and TURKS