While Yerevan and the entire Armenian nation was celebrating the diplomatic victory of Sèvres, the Kemalists and Bolsheviks were preparing their attack on Armenia.

The invasion of Armenia became the severe Turkish response to the Treaty of Sèvres and to the shaping of a united, independent Armenian state. Mustafa Kemal was convinced that the success of the Turkish nationalist movement required the political and military support of Soviet Russia and the removal of the threat of Armenian expansion into the regions of Trebizond, Erzurum (Karin), Bitlis, and Van.

To keep the enemy off guard, General KâzimKarabekir transferred his field headquarters from Hasankale back to Erzurum on September 2. There he welcomed the first formal Soviet delegation, which, because of Shalva Eliava’s illness, was headed by I. Upmal (Angarskii). In response to Upmal’s assurances of Soviet sympathy and support, as demonstrated by the 200 kilograms of gold the mission was carrying to Angora (Ankara), Karabekir emphasised Turkey’s importance in winning the friendship of the Islamic world for Russia and insisted upon the elimination of the Dashnak barrier separating Turkey from Russia.

In mid-September, 1920, the Turkish armies re-occupied those territories which had come under the control of the Armenian armies in June – the region of Olti, with its coal mines.

General Karabekir was concerned that if Soviet rule was established in Armenia before the Turkish army had occupied the mountain range around Sarigamish, recovery of any territory beyond the 1914 Russo-Turkish border would be impossible. Khalil informed Karabekir that the Red Army would invade Armenia between August 21 and 25 in the direction of Yerevan and Alexandrapol-Kars, and that he had given assurances of Turkish collaboration. Karabekir recommended that, in such a case, the Turkish army should advance toward Kars and as far as the Araxes River and Novo-Selim, whether or not Turkish help was requested.

Immediately after receiving from Yusuf Kemal Bey the terms of the Soviet-Kemalist draft treaty of August 24, 1920, Mustafa Kemal authorised General Karabekiron September 20 to occupy the province of Kars as far as Kaghzvan, Novo-Selim, and Merdenek and, if conditions permitted, even farther. The foremost objective was the destruction of the Armenian army. In order to ensure the neutrality of the Georgians, they should be led to believe that they would be allowed to have the lands they coveted in the region. Karabekir should communicate with the Georgian authorities to that end and in no case seize any of the Georgian-occupied territories in the three sanjaks of Batum, Ardahan, and Kars.

The command of the Armenian army appealed to Prime Minister Ohanjanyan, suggesting to protest to the representatives of the Allies in Tiflis, Britain and France, about the actions of the Turks. On September 14, the government discussed the situation in Kars province and the placing of military and civil authority in the hands of Bek-Pirumyan. Stepan Ghorghanyan, the governor of Kars, approached the government, demanding an investigation into the events at Olti and punishment for the guilty. He insisted that the reason for the defeat at Olti were the unpredictable conditions prevailing in the army. After capturing Olti in June, the Armenian army units and in particular the officers had taken part in looting. No action was taken on Governor Ghorghanyan’s reports and alarms.

In the reports addressed to the army command, General Artyom Hovsepyan accounted for the inglorious defeat of the Armenian forces by the unexpectedness of the attack. The Armenian forces under the command of Hovsepyan showed how it was possible to not defend the homeland. The military records and communiqués prove that the Armenian army did not fight in this phase of the war and continually retreated in panic under the pretext of “capturing better positions”. The army was fleeing and spreading panic throughout the province. On September 30, Kaghzvan was also handed to the enemy, without a shot being fired.

From September 27-30, the Turks also captured the Armenian part of Ardahan (the northern part was under Georgian control) and Merdenek. The Armenian population of Kars province fled with the army towards the fortress of Kars. A session of the Council of Ministers convened on September 28 in Yerevan. After discussing the situation at the front, the government decided “to delegate general Silikyan commander of the Kars front with the authority of commander in chief” and “temporarily give the governing of the Kars military operation in its entire structure to the War Ministry.”

On September 30 the bureau-government of the Republic of Armenia, declaring the country under a state of siege, established martial law, issued mobilisation orders for men up to thirty-five years of age, and adopted stringent measures against desertion.

One of the government members, Simon Vratsyan who, together with another minister, Artashes Babalyan, had been sent to the Kars front, does not agree in his later writings with the widespread opinion that the Turks defeated the Armenians without meeting any obstacles, and that the Armenian army showed no resistance. “This opinion is the result of absolute ignorance. If one part of the Armenian army did not rise to the occasion, the other part showed wonderful examples of self-sacrifice, intrepidity, and patriotism. In particular, bloody battles took place at the Surmalu front, where the general commander was Dro [Kanayan]. In some places, fifty percent of Kuro Tarkhanyan’s soldiers were killed or maimed but did not retreat.”

Vratsyan considers the main reason for the defeat of the Armenian forces in Kars to be the psychology which had been produced by the Bolshevik-Turkish friendship. “On the one hand the Armenian people, extremely tired, destroyed, and yearning for peace wanted to believe the Bolshevik assurances that the Russians would not let the Turks perpetrate more massacres in Armenia, and on the other hand, the Armenian people had become despondent and demoralised, seeing that both the Turks and the Russians were fighting against them and they were incapable of resisting these two huge states with their small forces.”

Cabinet members Vratsyan and Babalyan were highly critical of Bek-Pirumyan and Hovsepyan, who had sounded the call to retreat at the first sight of the Turkish regiments. Vratsyan and Babalyan deplored the harmful rivalry between the civil and military administrations at Kars. They urged that Sepuh immediately be transferred to Kars; the Western Armenians making up much of the population had no trust in the generals, but would rally around Sepuh, whose prestige had soared since the suppression of the Bolshevik uprising in May.

Babalyan, who fell captive in Kars, subsequently wrote, “Our high command and officers’ corps were in the hands of people with pro-Russian orientation. Were generals Nazarbekyan, Silikyan, Hakhverdyan, and others really devoted to our independence? Many of them were very good Armenians, but considered an independent Armenia to be a temporary phenomenon, which would disappear under Russian influence. Ankara was working with Moscow’s approval.”

In the days of the Bolshevik riots of May 1920, Kars, including its Russian-speaking soldiers, was one of the regions that rebelled against the government. This occurrence also demoralised the Armenian army.

Vahe Artsruni, the Armenian government representative for immigration affairs, stayed in the city together with American missionaries until January 15, 1921. In his words, “Many, from the highest ranking soldiers to the privates, did not escape the bewitching claws of unrestrained propensity for looting, which was one of the main reasons for the failure of the Kars front. At the height of the battle, our volunteers preferred to stay at the rear and loot, rather than carry out their responsibility.” Artsruni also insists that there were moments of exemplary resistance on the Kars front, such as in the Sarighamish area, when the fourth division, under the command of Dmitrii Mirimanyan and Nesterovski, showed marvellous resistance, but were forced to retreat to Begli Ahmed village.

These were the only exemplary episodes. In general, the situation had become chaotic and ungovernable.

They were attacking the Armenian borders from the east, south-east, south-west, and west. Only the northern border was peaceful. Georgia agreed to maintain neutrality in the Armenian-Turkish war regions. A secret treaty was signed in Tiflis between Kâzim Bey (Özalp) and the Georgian government. Only on October 2 was Armenia informed that the Georgians had signed a secret treaty with the Kemalists.

Despite this, minister Ter-Minasyan was sent to Tiflisin mid-October with expectations of aid from the Georgians, to persuade the Georgian government “to fight with united forces against the dangers threatening Armenia and Georgia,” in Khatisyan’s words. “The Armenian government was taking it upon itself to protect the Turkish front, while the Georgians were to push back the Bolshevik danger. The British Commander Stokes was participating in those negotiations. The Georgians could not risk losing their neutrality. The Georgians did not accept our government’s proposal; the Ter-Minasyan mission was unsuccessful. The Georgians were not expecting an attack from the Turks and considered the treaty they had signed with the Bolsheviks to be reliable.”

After the loss of Armenia’s independence, it would be Georgia’s turn. In Tiflis, the Armenian representative Tigran Bekzadyan in his secret letter of October 26 to the foreign minister of Armenia, explains Georgia’s stance thus: “They do not consider the danger of Russia against us to be serious, and so they are not afraid that we may soon fall under their influence and become Soviet. The Georgians do not consider themselves threatened by Kemal. They are not going to fight with us, and so we must not place any hope on them at all. If they do not interfere with our mobilisation and transit and really simplify the export of certain important goods from here [Tiflis], and Batum, we must consider that to be the greatest assistance.”

The “assistance” of the European allies was limited to words of sympathy. “Armenia was left alone, in the true sense of the word,” writes Vratsyan with bitterness.

Armenia was forced to call upon its last forces.

Hundreds of men left their fields to volunteer for military service, and many soldiers absent without leave returned to their regiments. The crush of young men at the recruitment centres was so great that it was difficult to enlist and assign them properly. So many women volunteered as nurses that most had to be turned away.

A sense of urgency and cohesion prevailed as members of the bureau-government set out for the several fronts to lend encouragement and help inspire confidence: ministers Simon Vratsyan and Artashes Babalyan at Kars, Abraham Giulkhandanyan at Kazakh-Ijevan, SargisAraratyan at Surmalu, and Arshak Djamalyan and Gevorg Kazaryan at Alexandrapol, as well as parliament members Sergei Melik-Yolchyan at Nor-Bayazed, and HakobTer-Hakobyan and Hambardzum Terteryan at Ashtarak.

Prime Minister Ohanjanyan sent a telegram to the Armenian envoy Bekzadyan in Tiflis on September 30. “Under pressure from the enemy, we left Sarighamish and Kaghzvan. Kars is in danger. We are defending 700 versts with our own forces. Announce all this to the Allies and demand speedy help. Ask the Georgians for fuel at least for the organisation of transport.”

On October 1, Ohanjanyansent a telegram to Bekzadyan: “Our forces are concentrated in the Kars and Begli Ahmed regions. The entire population has risen up. All the ministers have left for the front and to be amongst the people. Demand immediate aid from the Allies. The Turkish-Bolshevik collaboration is evident.”

The ruling ARF-Dashnaktsutyun called upon the party members. The ARF Bureau’s statement read: “Friends, the enemy is once again knocking onour door. Bloody events are taking place in Sarighamish. The Turks want to drown Armenia in blood and destroy the Armenian nation. Each comrade is obliged to put himself at the party’s disposal and immediately perform the instructions given to him. Comrades – to work, to the front!”

Prime Minister Ohanjanyan addressed the nation, recalling the heroic days of 1918 at Sardarapat: “I summon you to a holy war. The enemy will be defeated only on the day when all of you stand as one person ready to fight and die.”

Though frequently smarting under the overbearing attitude of the Dashnaktsutyun, the Armenian parties to the right (Zhoghovrdakan-Populist and Sahmanadir Ramkavar-Constitutional Democratic) and the left (Hunchakist-Social Democrat, Social Democrat Labour, and Social Revolutionary) joined the ruling ARF on October 1 in the formation of an inter-party council and issued individual and joint appeals for a national crusade against the unholy alliance of Turkish pashas and Bolshevik commissars.

Until the first week of November, each day the front page of Haraj read:“TO THE FRONT: TO WAR”. “Be prepared, Armenian nation, the Turkish danger is coming. Be prepared, Armenian worker. Whoever is not with us is our enemy. Whoever flees is a traitor. Dashnak comrades, our nation’s centuries-old adversary is coming.”

In Kars, the Armenian authorities and the Armenian soldiers did not understand each other, not just because the Armenian military establishment were Russian-speakers and had little knowledge of Armenian, but because the battle had created such a moral-psychological situation for the local authority that, in those circumstances, it was only possible to be defeated. Vahe Artsruni writes that the conflict between the civil and military authorities in Kars was old. “The conflict, to put it concisely, is between governor Ghorghanyan and commanders Bek-Pirumyan and Hovsepyan.”

The governor of Shirak, GaroSasuni, explains in detail: “High ranking soldiers headed by Nazarbekyan did not like irregular and uneducated soldiers such as Sepuh and Dro, whereas middle-ranking soldiers believed in them and wanted to see them in responsible, commanding positions. Sepuh played a big role in the suppression of the May riots and in particular on the Kazakh front, making the invasion of the reds into Armenia impossible. The influence of the commander of the Surmalu front, Dro, had declined as a result of his departure from Karabakh and Zangezur during the May riots, under pressure from the Red Army. When the Armenian-Turkish war began, in the last week of October, Dro cleared the region of Margara-Igdir with his force of three thousand regulars and one thousand civilians, and the Turks retreated towards the slopes of Masis.”

On October 5, British supreme commander, Colonel Stokes, and the British representative in Yerevan, Gracey, arrived in Kars. The military and civil authorities and thousands of local inhabitants gave them a formal welcome at the station. Ministers Vratsyan, Babalyan, governor Ghorghanyan, and the commander of the Kars military front, Pirumyan, were amongst those meeting Stokes and Gracy.

The British colonel, who had come in person to become acquainted with the situation at the front, visited the Begli Ahmed military unit, gave a speech to the soldiers, not forgetting to mark that the Armenians were the first Christian nation in the world. On the same day, refusing an invitation to dinner, Stokes left Kars. Before leaving, the British colonel, in his not very fluent French, expressed, “We will dine another time. I can see that your situation is serious. May God protect you.”

On October 6, the Armenian envoy in Tiflis communicated that there had been a protest march past the missions of the allied states by around ten thousand demonstrators. The demonstration in front of the Soviet mission had been severe, yet polite. The response of the Soviet representative, Leonid Stark was interesting. He reported to the demonstrators that if the Armenian government agreed to accept Mustafa Kemal’s proposal, that is, to accomplish the conditions set by it through negotiations with Bolshevik mediation, then probably this attack by the Turks would not have occurred.

Stark added that the ARF had become a tool of the Entente, and it was now up to the Armenian people to decide either to be with revolutionary Russia or to allow the old ways to continue. Russia had offered to mediate between Armenia and Turkey, and despite the fact the no positive response had been received from the Armenian government, the offer still stood. The crowd of Armenians chanted, “You lie! You lie! Karabakh, Zangezur, Nakhijevan, and Kazakh were unmistakable examples of Soviet Russia’s ‘friendly intervention’.”

In Europe, meanwhile, the monotonous Armenian appeals for allied military intervention fell on deaf ears. Beginning on October 5, Avetis Aharonyan wrote each of the Allied Powers, the League of Nations, and scores of politicians, statesmen, and intellectuals to point out that the Turks were striving to conspire with the Bolsheviks in order to overrule the Treaty of Sèvres with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Armenia could have defended itself if it was not simultaneously pinned down on three fronts by the Turks, Azerbaijani Tatars, and Russian Bolsheviks.

The fate of Armenia’s First Republic had been decided. On October 2, Gevorg V, the Catholicos of All Armenians, once again appealed to the Armenian people: “Two years of life has taught us that we must defend our homeland; the foreigner has not helped us and will not do so. Go and fight bravely. Clear the road to the charred remains of your homeland Mush and Sasun, Surp Karapet, and Aghtamar, with your swords. And you, Armenian sons of the land of Ararat, sons of Vagharshapat, Oshakan, Ashtarak, Sardarapat, Aparan, Shirak, Tzaghkatsor, and Gegharkunik, leave your homes and fly to the borders, your freedom is at risk. Remember Zeytun and Sardarapat. Defeat the enemy so that the flag atop Masis [Ararat] remains steadfast.”

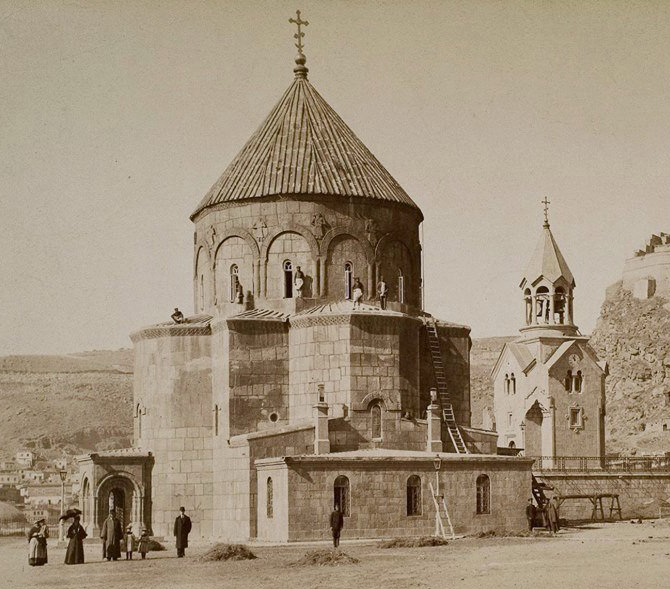

Bishop Garegin Hovsepyants27 had left the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin and was travelling around, cross in hand, from garrisonto garrison, unit to unit, talking to the soldiers, giving communion to them, and inspiring them. On October 12, Bishop Garegin read the official epistle of the Catholicos of All Armenians for the victory of the army in the historic monastery of Arakelots in Kars. The bishop conveyed the situation in Kars to the government in Yerevan, “The army and the citizens charged me with declaring that they are ready to resist with their last breath the unlawful enemy and expel him from the borders of our sacred fatherland.”

But after several weeks, at the end of October, Karabekir’s armies occupied Kars almost without resistance. Governor Stepan Ghorghanyan stated, “Kars fell, but it was not defeated; it became the victim of our criminal negligence.”

The final collapse of the capital of Bagratid (Bagratuni) Armenia was in the autumn of 1920. The third largest city of the First Republic of Armenia has now been under Turkish occupation for over ninety years.

An official appeal was sent out by the government on October 31 on the occasion of the fall of Kars: “Our forces, unable to resist the attack of the enemy, have mostly retreated after the battle. The remaining small units in Kars have surrendered. The city and its fortifications are in the hands of the Turks. In the face of this dreadful situation, the government asks you, citizens, do you want to fight against the invading enemy, do you desire to defend you homeland’s independence, the lives of the people, your honour? For the government, there can’t be two answers to this question. It has decided to fight to the last, until death.”

On November 1, Babalyan, who had fallen captive on the day of the fall of Kars, wrote, “Military operations must cease as soon as possible and peace talks must start immediately. Agreement must be arrived at with the Anatolian government. There must be an end to the bloodshed of years which is destroying our people. Generals Pirumyan, Araratyan, Kazaryan, and Colonel Vekilov agree with this proposal.”

These four high-ranking soldiers had also fallen captive in Kars. Karo Sasuni writes that, although the decision to sign a peace treaty had been taken, “There was no one who would commit to taking that step.”

Most of the 2,000 Armenian junior officers and enlisted men who fell prisoner were taken to the railway station and then transported for confinement and labour in Erzurum. Subsisting under extremely harsh conditions during the winter of 1920-1921, many of these men died in captivity. Also taken prisoner were generals Bek-Pirumyan, Kazaryan, and Araratyan, colonels Vekilov, Ter-Arakelyan, and Babajanov, minister Babalyan, vice-governor Ruben Chalkhushyan, mayor Hamazasp Norhatyan, and Bishop Garegin Hovsepyan, among others. In October 1921, nearly a hundred Armenian officers and more than 500 enlisted men were released and returned to Armenia.

Armenians and Turks

This book covers almost the whole spectrum of Armenian-Turkish relations, including the different attitudes of Diasporan circles and masses to the past, present, and future relations with the Turks. Tatul Hakobyan’s work is a smooth mix of history and journalism. This extremely complex and significant period of history is presented coherently, simply, in an easy to follow narrative that links together the various periods during the tumultuous 100 years beginning in 1918. Armenians and Turks, is packed with political insight, historical revelation, and even a poetic vision of a complicated relationship which unfolded, over a century, between two peoples. Hakobyan has established himself as an indispensable journalist, expert, and scholar of this ongoing saga. Written in the journalistic style using strict standards of scholarship, the author has evidently undertaken wide-ranging research. This book is of great interest not only to historians, diplomats, or experts who study issues of Armenian-Turkish relations and their impact on the future of the South Caucasus, but also for a wide range of readers.

This book covers almost the whole spectrum of Armenian-Turkish relations, including the different attitudes of Diasporan circles and masses to the past, present, and future relations with the Turks. Tatul Hakobyan’s work is a smooth mix of history and journalism. This extremely complex and significant period of history is presented coherently, simply, in an easy to follow narrative that links together the various periods during the tumultuous 100 years beginning in 1918. Armenians and Turks, is packed with political insight, historical revelation, and even a poetic vision of a complicated relationship which unfolded, over a century, between two peoples. Hakobyan has established himself as an indispensable journalist, expert, and scholar of this ongoing saga. Written in the journalistic style using strict standards of scholarship, the author has evidently undertaken wide-ranging research. This book is of great interest not only to historians, diplomats, or experts who study issues of Armenian-Turkish relations and their impact on the future of the South Caucasus, but also for a wide range of readers.

Paperback: 435 pages,

Language: English, Second Revised Edition

2013, Yerevan, Lusakn,

ISBN 978-9939-0-0706-9.