The Armenian Mirror-Spectator

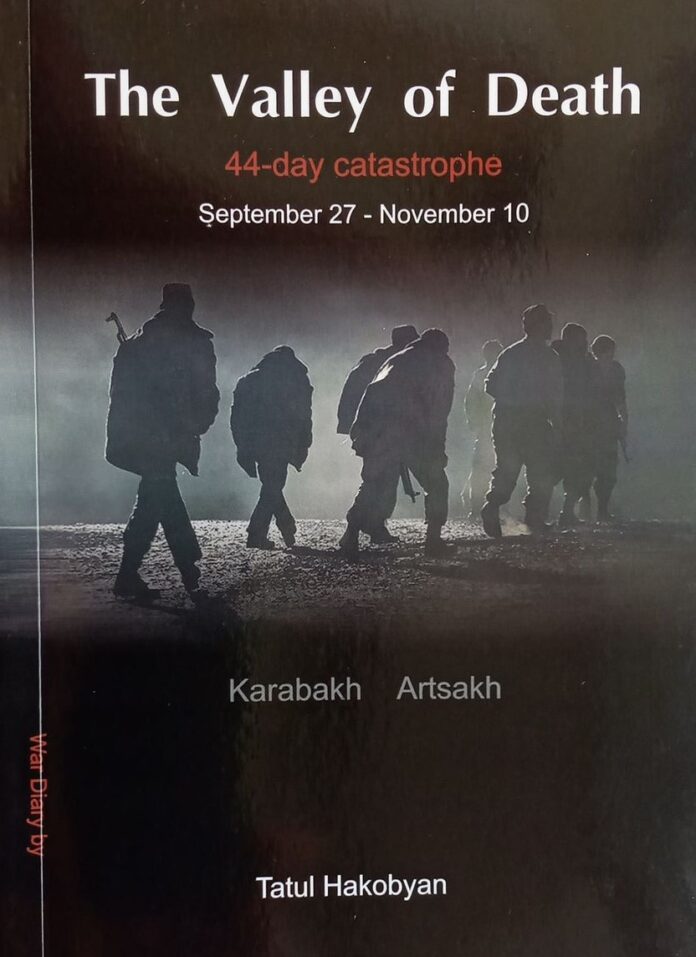

There are still many mysteries about what happened during the 2020 44-day Karabakh war, though the results of the war are clear. The collective mind of the Armenians is still digesting the significance and impact of the war and the defeat, with differing views often expressed in severe fashion. Journalist Tatul Hakobyan wrote frequently during and after the war from the front lines in the Armenian media, and has given many public talks, including in the United States, after the war. His collected writings on this topic were published first in Armenian, and then, last year, in English under the title The Valley of Death: 44-Day Catastrophe, September 27-November 10. War Diary (Yerevan: Lusakn Publishing House, 2021). Arsen Kharatyan, founder of Aliq Media, translated the majority of the 335-page book from Armenian into English, with a small number of pieces having been translated by Vahe H. Apelian.

This volume is not a monographic study. Instead, it is an anthology of news articles, interviews and opinion pieces by Hakobyan, who after graduating Yerevan State University’s Department of Journalism and the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs in Tbilisi, wrote as a correspondent for the Armenian and diasporan newspapers Ankakhutyun (1991-95), Yerkir (1998-2000), Azg (2000-2005), Aztag (2005-2016) and Armenian Reporter (2008-9), a columnist or political observer for the Radiolur news program of the Public Radio of Armenia (2004-2008), the online Aliq Media (currently), and CivilNet online television (for the Civiltas Foundation) (2009-2022). Since 2014, he has been a coordinator of the Ani Armenian Research Center.

Kharatyan in his preface notes that “This work shows how the official information provided to the public by Armenian and Karabakh officials during the war misled and confused our nation, when the realities on the ground were far worse from [sic] what we were being told.” In his “Author’s Note,” Hakobyan writes that he was unable to publish many of his reports in real time as a result of martial law in Armenia, especially as they contradicted the “official line” of the government. He published them only after the November 10, 2020 trilateral ceasefire agreement signed by Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia.

Around half the articles in the book are about the developments of the war, and the other half provide historical information and broader context. A number of pieces pay special attention to the 2016 April four-day war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and the newest pieces cover developments up through February 2021. The articles are presented in reverse chronological order, starting with the most recent. Five texts of negotiation proposals and agreements on Karabakh are appended at the end of the volume.

Hakobyan raises important questions on many topics. Most pressingly, what will the long-term fate of the population and remaining territories be of the Artsakh Republic? He finds three possible ways to ensure the security of the Armenian population there. The Russian peacekeeping force might stay for 50 instead of 5 years, and make Karabakh a Russian territory, as it was in the 19th century. Armenia may become powerful enough to provide Karabakh with security guarantees. An agreement might also be reached between Armenia and Azerbaijan giving Karabakh an in-between ambiguous status which allows it de facto independence.

If Azerbaijan fully controls the territory, Hakobyan can only picture a nightmare scenario of depopulation or massacre of the local Armenians. He mentions the possibility of Armenia regaining full control of Artsakh, and without directly commenting on its likelihood, notes that Armenia is unable to defend its own borders at present.

He emphasizes that Armenia can never rely on any third party to ensure its security. Russia has historically left the region and abandoned the Armenians a number of times, for example. Hakobyan is a critic of grand nationalistic territorial claims. Instead, he recommends reaching an understanding with Armenia’s Turkish and Azerbaijan neighbors directly and notes “today, regardless of Karabakh’s status, the highest priority should be making sure that Armenians continue to live in Artsakh.”

Any agreement must be acceptable to Armenians as well as Azerbaijanis, he writes, otherwise a new war to rectify the situation is inevitable.

Responsibility for the 2020 Defeat

Hakobyan does not shy away from speaking his mind. Hakobyan is hard on Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and his government and calls them “malefactors” for not stopping the war when there was an opportunity in October 2020. He writes about this topic in multiple articles. He accuses the ruling elite directly in one piece: “You don’t seem to realize that it was you who sent to a deathtrap a whole generation of our nation born in 2000 and 2001.” He blames the leadership also for the loss of Shushi, declaring “Armenia’s current government has made fatal mistakes, which in some instances can be qualified as criminal.”

He is referring to Pashinyan refusing the Russian offer to stop the fighting on October 19-20, if Armenia would allow Azerbaijani refugees to return to Shushi. While it appears after the fact that Pashinyan was preferring a Shushi under Azerbaijani control to a Shushi under Karabakh/Armenian control populated by a large majority of Azerbaijanis, Hakobyan speculates that Pashinyan in fact miscalculated that the Armenians could regain Shushi militarily.

He also writes that the military and political leadership of the Artsakh Republic bear an important share of responsibility.

Hakobyan notes that Onik Gasparyan, head of Armenia’s joint chiefs of staff during the war, declared as early as the fourth day of the Artsakh war at the Armenian National Security Council meeting that the war needed to be stopped within 2-3 days because losses will otherwise continue and the basis for a diplomatic solution will progressively get weaker. In other words, Pashinyan was told by the military that Armenia could not win this war militarily, so he should have sought alternative solutions.

On a broader scale, Hakobyan finds that Armenians tend to want to find culprits responsible for their defeats instead of taking responsibility for their own errors. For the most recent war, Nikol Pashinyan’s regime is being blamed by many, along with a Russian-Turkish conspiracy. However, every Armenian bears a share in the defeat, Hakobyan writes, including the previous Armenian regimes, and maximalists in the diaspora dreaming of Hay Tad (the Armenian Cause) as embodied in the Treaty of Sevres.

Pashinyan himself has attempted in speeches and writings such as “The Origin of the 44-Day War” to blame his predecessor regimes in order to plant the idea that the war was inevitable. Hakobyan points out that Pashinyan, unlike his predecessors, was insisting that the only solution to the conflict was the independence of Artsakh, with the latter participating again directly in negotiations, and Russia had offered a plan which would have avoided war and left Armenians in a better position than they are now.

Hakobyan includes himself in the list of those responsible, declaring: “What about the author of these lines, who was afraid to write about the possibility of peace every day, because the ultra-nationalists would accuse him of pacifism, defeatism, even betrayal and Turkism?”

Why Is Pashinyan Still in Power?

Hakobyan speculates in one article that the public is supporting Pashinyan largely due to a lack of a credible alternative political force in Armenia, while it rejects the representatives of the prior regimes. The shock of the war defeat causes despair, while Hakobyan feels the large protest movements of 2018 in a way discharged the accumulated collective anger of the masses and they are not ready for new mass movements. Finally, Hakobyan writes that Russia wishes to keep Pashinyan in power in order to carry out the agreements it has brokered with Armenia and Azerbaijan, even if against the interests of the Armenian people, and it did not look kindly on the street protests immediately after the war.

In another article he observes that Pashinyan was not able to make good use of his historic opportunity after coming to power, and the first signs of that were his approach to politics based on personal affiliation and his abandonment of institutional reform. His calls on the populace to block the entrance to the courts or blockade the National Assembly, Hakobyan said, indicated “he was rejecting the opportunity to transform from a populist politician to a state leader.”

Turkish-Armenian Relations

Hakobyan is the author of a book on Turkish-Armenian relations called View from Ararat: Armenians and Turks (2012). Some of his articles in his new book also examine this topic. He is a proponent of normalizing direct relations without the mediation of Russia or other third parties. He gives historical examples of how not talking with Turkish Nationalists in the first republic was with hindsight considered an error by leaders like Aleksandr Khatisyan. Hakobyan writes, however, that in recent times, during two prior attempts at the normalization of Armenian-Turkish relations, Turkey brought up three preconditions: Armenia’s recognition of Turkey’s current borders and territorial integrity, abandonment of support for international recognition of the Armenian Genocide, and withdrawal from territories in the Karabakh conflict zone. If the latter issue has largely been resolved by the war, Hakobyan questions whether Armenia is ready to act on the other two, since frank public discussion is not possible on these issues.

Hakobyan wonders whether Armenia will passively allow Turkey and Russia to continue to divide up the region together in a cooperative manner, and fears ending up with a capitulation like that of November 10, 2020, or a disastrous treaty like that of Alexandrapol 100 years ago.

War Coverage

Hakobyan has many pieces written during the recent war, which are composed with an immediacy conveying his emotions. For example, when exposed to rocket attacks, he writes, “When attacks like these start, your knees start to shake, and the only thing you can do is stay in a shelter waiting for the next rocket, and the next one, until it stops.” At the end of every day, he and other journalists in Stepanakert would see minivans bringing in the dead bodies of soldiers, while in the mornings they could see the bloodstained barrows leaning over the walls of the morgue.

He sadly wonders about the fate of many of the people he encountered during the war, especially in places like Hadrut that were lost to the Azerbaijanis. He writes that the voices of wounded soldiers, being brought in such large numbers to a Hadrut hospital that often first aid had to be given by nurses in the yard while the dead would be taken to an adjacent building, ring in his ears to this day, and certain images remain seared in his mind, like that of a soldier who died with his AK-47 on his chest containing one last bullet.

As noted above, he uses his notes to write after the war what he could not write in real time. While official Yerevan spoke about victory and destroying the enemy, Hakobyan saw signs of chaos and retreat but was unable to write publicly of the panic evacuation of Shushi and even of people from Stepanakert. On November 7, at Azat Village of Vardenis past the Armenian border, Hakobyan wrote, “For 10-15 minutes I was standing under the rain and snow looking at people running away. Who ordered this evacuation? How and why should people escape at a time when around 30,000 of our servicemen are on the frontline? Why are we leaving our boys alone, whose mothers are waiting for news from their children in Yerevan, Gyumri, Vanadzor, Tashir and elsewhere. Those 10-15 minutes were unbearable, filled with countless thoughts.”

Hakobyan with hindsight expresses his regret at not speaking up openly to combat fake Armenian government propaganda, in particular about Armenian forces taking back Jebrayil and the Khodaferin bridge, the prevention of an Azerbaijani offensive near Kubatlu, and the fall of Shushi.

Hakobyan also provides important information on prior clashes. He went to Talish and southern Artsakh and attempted to ascertain how much territory had been lost to Azerbaijan during the April 2016 four-day war. While his estimates were not precise, they served a useful purpose because the actual figures became politicized. Then President Serzh Sargsyan, for example, gave varying figures, decreasing over time after the event, from 800 to 400 hectares. After Pashinyan came to power, Hakobyan correctly writes, his proponents presented the war as a defeat, while Sargsyan’s supporters presented it as a victory.

History

Hakobyan frequently makes historical comparisons of the current situation with that of Armenia in previous eras, particularly during Tsarist rule, the Soviet period, and the first republic. Miscalculations similar to those committed during the first republic were among the causes of the 2020 defeat, he observes, including overestimating Armenian strength, hoping for third party support and underestimating the adversary.

There is much relevant historical information for non-specialists, such as, for example, the changes in the borders of Armenia during the Soviet period, largely in favor of the Soviet neighboring states of Georgia and Azerbaijan. Such historical comparisons and background information are particularly useful when attempting to understand issues such as the disputes over the borders of the current Republic of Armenia.

Several articles in this volume discuss various aspects of the negotiations from the end of the first Karabakh war in 1994 until the present, both conducted by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s Minsk Group and by individual powers like Russia.

Some of the most moving parts of the book concern Hakobyan’s reminiscences about his native village of Dovegh, nearby Noyemberyan, and the surrounding areas of Tavush Province. The first Karabakh war began there, not actually in Karabakh, in 1990. Hakobyan relates the sad story of his cousin, taken captive by Azerbaijanis while driving to work in his car, whose fate remains unknown to this day. Another cousin was killed in his vineyard in Dovegh Village after the active phase of the war had ended. Twenty villages of Tavush remained within reach of Azerbaijani snipers even after the first war and continued to suffer losses through three decades of a liminal situation, neither war, nor peace. Hakobyan also describes the military escalation of July 2020 which took place in Tavush.

Clashes took place between Azerbaijanis and Armenians there even in the Soviet period. As a child, Hakobyan witnessed a dispute over the use of forest and water at the border in 1984 or 1985 that led to fighting and the intervention of Moscow.

There are some articles dealing with general themes like demography. Hakobyan notes that when President Serzh Sargsyan spoke about increasing the Armenian population to four million by 2040, it sounded unrealistic and like a joke to many, whereas Prime Minister Pashinyan’s announcement twice that Armenia will have a population of five million by 2050 appeared even more unfounded due to an aging population, shrinking birthrates, and no major process of repatriation. Hakobyan remarks moreover that Armenia and its diaspora failed in repopulating Artsakh, which is one of the least densely populated areas among both recognized and unrecognized states.

The Journalist as Participant

We learn from the book that when Hakobyan traveled to Artsakh during the war, he not only carried out his journalistic duties, but also tried to be helpful to the local population in other ways. Sometimes, he would be given small presents like packets of cigarettes to distribute to soldiers. When individuals asked him for help in finding their relatives who had been serving as soldiers, he would put them in touch with various relevant officials. Other times, he served as an intermediary for arranging assistance on a larger scale. In early October, for example, after returning from Artsakh, he went to his birthplace of Noyemberyan and spoke with the mayor and other leaders about the difficulties facing Martuni (in Artsakh), including loss of all electrical power. The latter decided to send 12 electricians to Martuni, as this was a field, so Hakobyan called Artsakh Foreign Minister Masis Mayilyan, who in turn connected Hakobyan with the head of the Artsakh Energy department to facilitate the work of the 12 electricians. Within five days electricity was restored in Martuni, and they also renovated the Martuni Cultural Center and cleaned up the surroundings of the local Monte Melkonyan statue.

The book contains powerful photos, many of which were taken by Hakobyan, but they deserve better quality reproduction. The translation into English is readable but with plentiful minor grammatical and stylistic flaws and typographical errors which a good editor with native mastery of English could have fixed. In such a collection of articles, naturally there is some repetition of information, but beyond this, an entire chapter or article was repeated in whole (pp. 287-97 and 298-306). Furthermore, in another chapter, five paragraphs from pp. 219-220 are repeated verbatim on pages 221-222.

Notwithstanding these flaws, Hakobyan’s volume is a good starting point for understanding the 2020 war and its aftermath.