Avetis Nazarbekian; “If the Armenians must die, they will die, not as slaves, but as free men”

Until 1895, Paris remained a place of exile for the Young Turks, including the most famous of them, Ahmed Rıza, who founded the Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (OCUP) in this period. Rıza had gathered only a small group of Young Turks around him, but it was a very select one: it included Dr. Nâzım, a native of Salonika, who joined him in 1894 in Paris, where he also hoped to complete his medical studies, and Ahmed Ağaoğlu (Agayev), a native of Shushi (the capital of Karabagh) who took courses in history and philosophy at the Sorbonne and the National Institute of Eastern Languages and Civilizations.

Agayev (1869–1939) became one of the ideologues of Turkish nationalism and an eminent member of the CUP’s Central Committee; as such, he was arrested and deported to Malta by the British in 1919. A leader of the Social Democratic Hnchak Party, Stepanos Sapah-Giulian, often met with Agayev during his stay in Paris.

Among the Armenians in Paris in the same period, Sapah-Giulian was undoubtedly the most interesting figure. A leader of the Hnchak Social-Democratic Party (SDHP), Sapah-Giulian was the moving spirit behind the Hnchak club in Paris. Here he rubbed shoulders with the Young Turk exiles, whom he claimed to know better than anyone else because he had had dealings with them for so many years.

In early 1895, in Parisian political and intellectual circles, conversation turned on the appropriate reaction to the anti-Armenian massacres perpetrated in Sasun in summer 1894 and the publication, in a British parliamentary Blue Book, of the damning conclusions of the European consuls who had served on a commission of inquiry into these events. The Sultan, many said, had to be confronted with a demand for “reforms” in the eastern provinces of Asia Minor that would put an end to the “insecurity” reigning there.

For the first time, the Parisian Young Turks were forced to consider the vexing question of the “reforms” that the European powers were seeking to impose on the Ottoman Empire. With this question, it was their conception of the Ottoman state, and the place and status of non-Muslim elements in it, that was put to the test. The publication of an article on the reform plan of “11 May 1895,” in the Parisian daily Le Figaro, led to a meeting between the Parisian SDHP activists and the Young Turks, headed by Rıza and Nâzım, who had just been elected treasurer of the CUP.

Sapah-Giulian’s account of their meeting shows that the two Turkish leaders were staunchly opposed to this reform plan – that is to say, hostile both to European interference in what they considered an internal Ottoman affair, as well as the creation of a special status for certain provinces of the empire. They continued to argue for a policy of centralization, contrary to the Hnchaks, who simply denounced the tribal system and the violence prevailing in the eastern provinces and condemned the Sasun massacres.

What is more, the official leader of the Young Turk movement, Ahmed Rıza, rejected the revolutionary methods espoused by part of the anti-Hamidian opposition. He advocated, rather, a conservative policy that was ultimately not very different from the sultan’s. However, Rıza needed support from the Armenians, among others, in order to make his political project credible in Parisian circles. He therefore asked to meet with Nubar Pasha, an Armenian from Smyrna who had served as Prime Minister of Egypt and was the father of the Egyptian reforms, notably the creation of mixed courts.

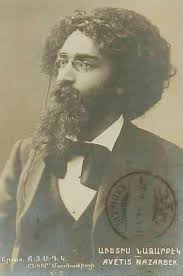

Rıza doubtless hoped to profit from the Egyptian pasha’s many connections to French politicians, and from his generosity as well. In fall 1895, the “Armenian Students of Paris” organized a lecture in a hall in the city’s Grand Orient lodge. The invited speaker was Avetis Nazarbekian of London, one of the SDHP’s founders. The lecture and the response to it offer us an opportunity to evaluate the positions taken by the Parisian Young Turks on the most recent persecutions of the Ottoman Armenian population.

Nazarbekian denounced Hamid’s policies, especially the generalized massacres of October and November and Europe’s indifference to them. “If the Armenians must die,” Nazarbekian concluded, “they will die, not as slaves, but as free men.” Yet, it was the part of his talk in which he questioned the Sublime Porte’s ability to govern its possessions that disturbed his Young Turk listeners, more than the crimes themselves. Sapah-Giulian later noted that the many Armenian students in the Young Turks’ ranks were surprised by their Muslim comrades’ negative reaction.

The massacres contributed heavily to turning Western public opinion against the Ottoman Empire. This pained the Young Turk exiles in Paris. The violence also helped bring about a radicalization of the Armenian Committees, whose leadership bodies had established themselves in London, Geneva, and Paris. The Young Turk movement nevertheless profited from the diplomatic crisis that followed the Armenian massacres.

Image – Avetis Nazarbekian

Note- This chapter is from Raymond Kévorkian’s book The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History, pp. 11-12