By Daniel Halton

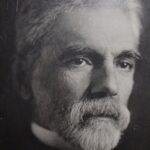

For more than half a century, Garo Nalbandian’s camera has captured the heart and soul of Jerusalem. From celebrations of faith, conflict and politics, papal and presidential visits, archeological discoveries and ancient history, Nalbandian’s catalogue of photographs is a chronicle of virtually every significant moment that has shaped the city from which he cannot part, enamored by the intersection of vibrant cultures and mystic beauty.

“I love Jerusalem,” he declares enthusiastically. “As an Armenian, Christian Jerusalem is sacred, holy land and I am proud of my community and I want to share it with the rest of the world through my pictures.”

Blessed with the energy and sense of wonder of a child, the gregarious photographer’s white hair and beard are the only traces of six decades of experience. As a photographer, his natural talent and skill with a camera have carried Nalbandian to international renown, sought after by foreign news crews including from CNN and ABC, Newsweek and National Geographic, as well as from Armenian, Greek, and Muslim religious leaders alike. His work has also been featured in television documentaries, movies, and books, while filling the racks of scenic postcards in every souvenir shop in Jerusalem.

Born in the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City in 1943, the son of Armenian refugees fleeing the Genocide, Garo began his photography career at the tender age of 13, as an unpaid apprentice at the Yergatian photography studio. His responsibilities consisted mainly of cleaning the studio and running errands, but he took advantage of every opportunity to assist the in-house photographers, eagerly teaching himself how to develop film and use a camera. Eventually his boss entrusted Nalbandian to take over the residency at the studio, albeit still unpaid.

Nalbandian’s first big break came not long afterwards when a journalist from the local Palestine newspaper called the studio urgently needing a photographer to cover the arrival of U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold. Despite being just 15 years old at the time, he picked up his cameras and went to the airport to cover the visit. Hammarskjold noticed the young photographer walking backwards in front of him among the throng of reporters and cameramen and stopped to ask Nalbandian whether his pictures would be any good. Garo confidently informed the Secretary-General of the United Nations that he would see for himself on the cover of the newspaper the next day! Of the dozen or more stills he took, indeed eight would be published. “Although my boss still didn’t pay me, it didn’t matter because soon we had three times the number of calls and customers asking to do studio portraits,” he recalled. “Soon other photographers began to recognize me and asked me to work with them. I remember I was making 8 dinars which was a lot at that time. I took 1 dinar for the whole month to pay for weekly expenses, sandwiches, and the cinema and I gave seven dinars to my father.”

Within a few years, Nalbandian launched his own studio and became both a sought-after expert in processing and developing color film and a skilled photographer, recognized for the quality of his work. In 1961 he photographed the visit of the Russian Orthodox patriarch, publishing his pictures for the first time in Newsweek and Time magazines. Over the decades that followed, Nalbandian would be granted a privileged window on history, chronicling seminal chapters in the city’s political, cultural and, especially, religious development. As the official photographer for the Catholic Custodian of the Holy Land, which together with the Greek and Armenian Patriarchates maintain the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Nalbandian’s pictures of the historic visits of Popes Paul VI, John Paul II, Benedict XVI and Francis, have been featured around the world.

He has also served as the Official Photographer for the Armenian and Greek Patriarchates and works closely with the Islamic Wakf or religious authorities in Jerusalem as well as the department of religious antiquities in Jordan. In each case, he is widely respected not only for his artistic portraits, but also his tact and discretion. When the Muslim Brotherhood wanted to record in pictures a closed conference, Nalbandian—a Christian Armenian—was entrusted over Arab photographers. “I take my job as a photographer very seriously,” he says. “I am not there to listen and give away secrets and that is why they trust me.” In the process, Nalbandian has since amassed one of the largest individual archives of published photographs on Christian and Islamic ritual in Jerusalem—a treasure trove of historic material, some of which continue to be published in numerous books and journals around the world.

There is one constant that has motivated him throughout his career: his reputation for consistently producing the highest quality and most artistic photographs. “Money does not matter to me. It has to be the best work,” he insists. “I could not live with myself if I took a bad photograph.” Even among award-winning pictures that have been featured in leading photography magazines, Nalbandian says there isn’t a picture of his where he does not think of some way it could have been improved.

The seasoned photographer is not only respected for the quality of his work, but has also been widely praised by news organizations around the world for his unparalleled connections, knowledge and instincts covering conflict and crisis as a photojournalist. Where other camera crews have been denied access, Nalbandian has always been able to persuade, cajole and negotiate entry to an otherwise closed meeting or unique vantage point. He recalls following a protest during a visit of King Hussein of Jordan in 1967, Prince Hassan waving a machine gun at the press ordering them not to take pictures. Undeterred when the King walked by Nalbandian stood up and asked permission to take a photograph to which the King obliged.

Often at personal risk, where reporters have dared not venture, Nalbandian bravely sought to portray the often brutal reality of life in a war zone. “It’s important to me to reflect exactly the story as it happened, even it means taking risks. It is very difficult to witness the aftermath of an explosion up close when there are victims including women and children, images that television cameras don’t typically air, but it is important to show the true extent of the conflict.”

While his Armenian background has helped open up many doors, as a photographer in Jerusalem, his job is perhaps more challenging than virtually anywhere else. Surrounded by communities in conflict and further complicated by official restrictions on non-Jewish residents, Garo had to wait close to 15 years to be issued an official press card. To this day, he is still not considered a citizen of the country in which he was born and has always lived. “I still don’t have citizenship as an Armenian, I have a laissez-passez document and a Jordanian passport from 1967 that I keep renewing for foreign travel purposes.”

While he has watched with great sadness over the years his fellow Armenian friends and colleagues leave Jerusalem in search of a better standard of life in Europe and North America, Nalbandian has not once considered abandoning the community and city he loves, despite lucrative offers to work in the United States. When not on assignment, he can be found with his camera patiently waiting for just the right conditions to capture a stunning landscape of the city he calls home. Among his most famous photographs, there is one of Bethlehem clearly visible below the mountains of Jordan, bathed in the soft glow of the late afternoon light when the haze that usually obscures the mountainous backdrop was momentarily lifted. He says he waited 8 years for just the right conditions and colors to capture the scene so vividly, a true labor of love.

After six remarkable decades behind a camera lens, capturing both the beauty and brutality of this ancient city, Nalbandian’s passion for his craft has never waned. Of all the historic events he has chronicled during that time, there is but one subject that has eluded his camera, one he dreams he will witness during his lifetime. “The most important thing for me that I wish is to see peace in Jerusalem.” Until then, this living treasure remains determined to make sure the history of his home is not forgotten.