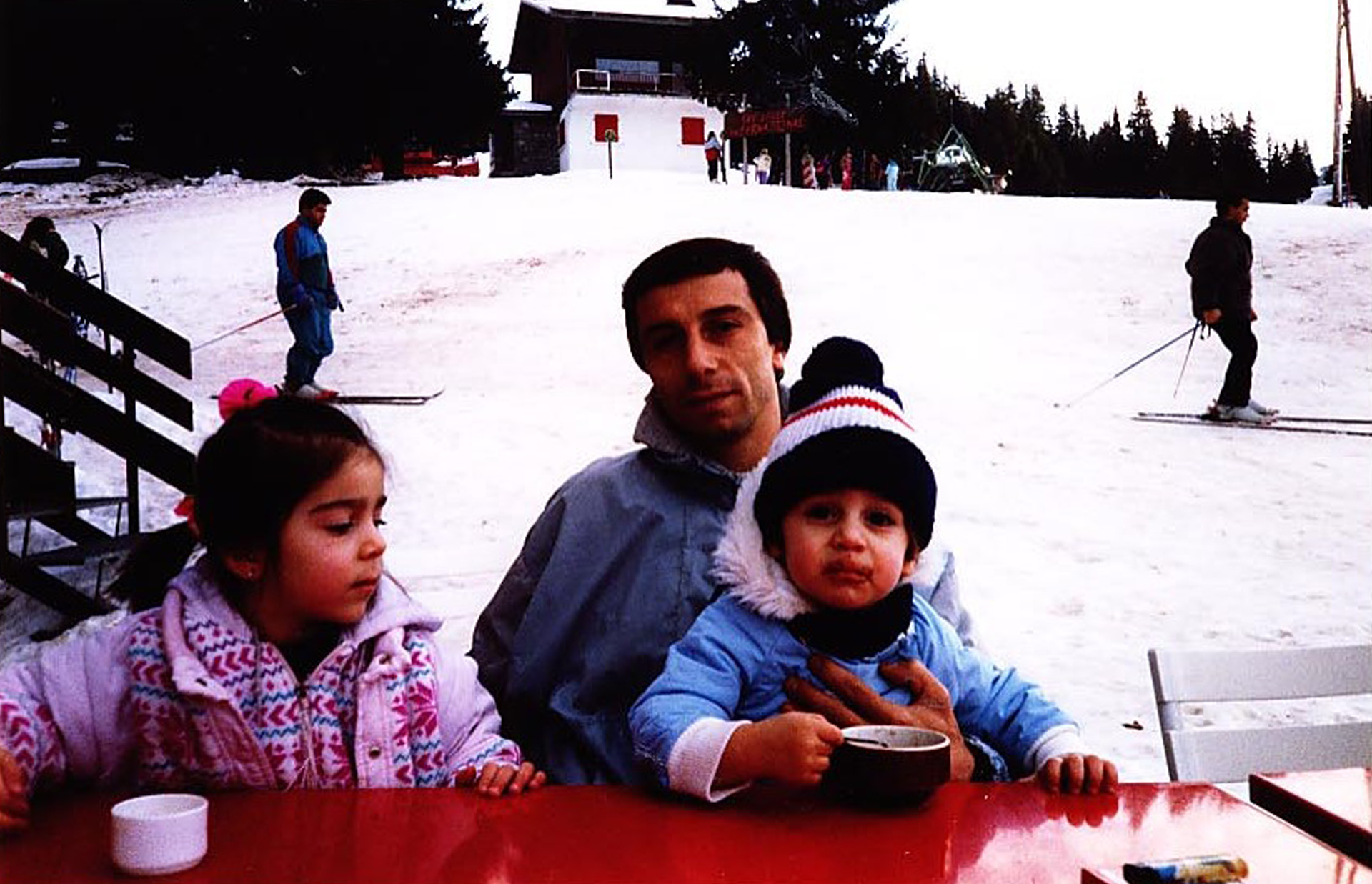

One of my earliest memories is begging my father, Hamlet, to take me to training with his football club in France. I was maybe five years old. In the ’80s, before I was born, my dad played in the old Soviet Top League in our home country of Armenia. He was a small but very quick striker. Soviet Soldier magazine actually honored him with its “Knight of Attack” award in 1984.

In 1989, when I was just a baby, we moved to France because of some conflicts that were brewing in Armenia. My father played five years for Valence in France’s second division. I’d always cry when he would leave for training. Every morning I’d say, “Dad, take me with you. Please, please take me with you!”

At that age, I didn’t really care about the football yet, I just wanted to be with my father. But he didn’t want to be distracted during training by worrying about me running off, so he came up with a clever plan to fool me.

One morning, I said, “Dad, take me to training.”

He said, “No, no. There’s no training today, Henrikh. I’m going to the supermarket. I’ll be right back.”

He escaped to training, and I waited … and waited.

He came back home after a few hours. No grocery bags.

I lost it. I started crying.

“You lied to me! You didn’t go to the supermarket! You went to play football!”

My time with my father would be very meaningful, but also very short. When I was six years old, my parents told me that we were moving back home to Armenia. I didn’t really understand what was happening. My father had stopped playing football, and he was at home all the time.

I didn’t know it, but my father had a brain tumor. Everything happened very fast. Within a year, he was gone. Because I was so young, I didn’t completely understand the concept of death.

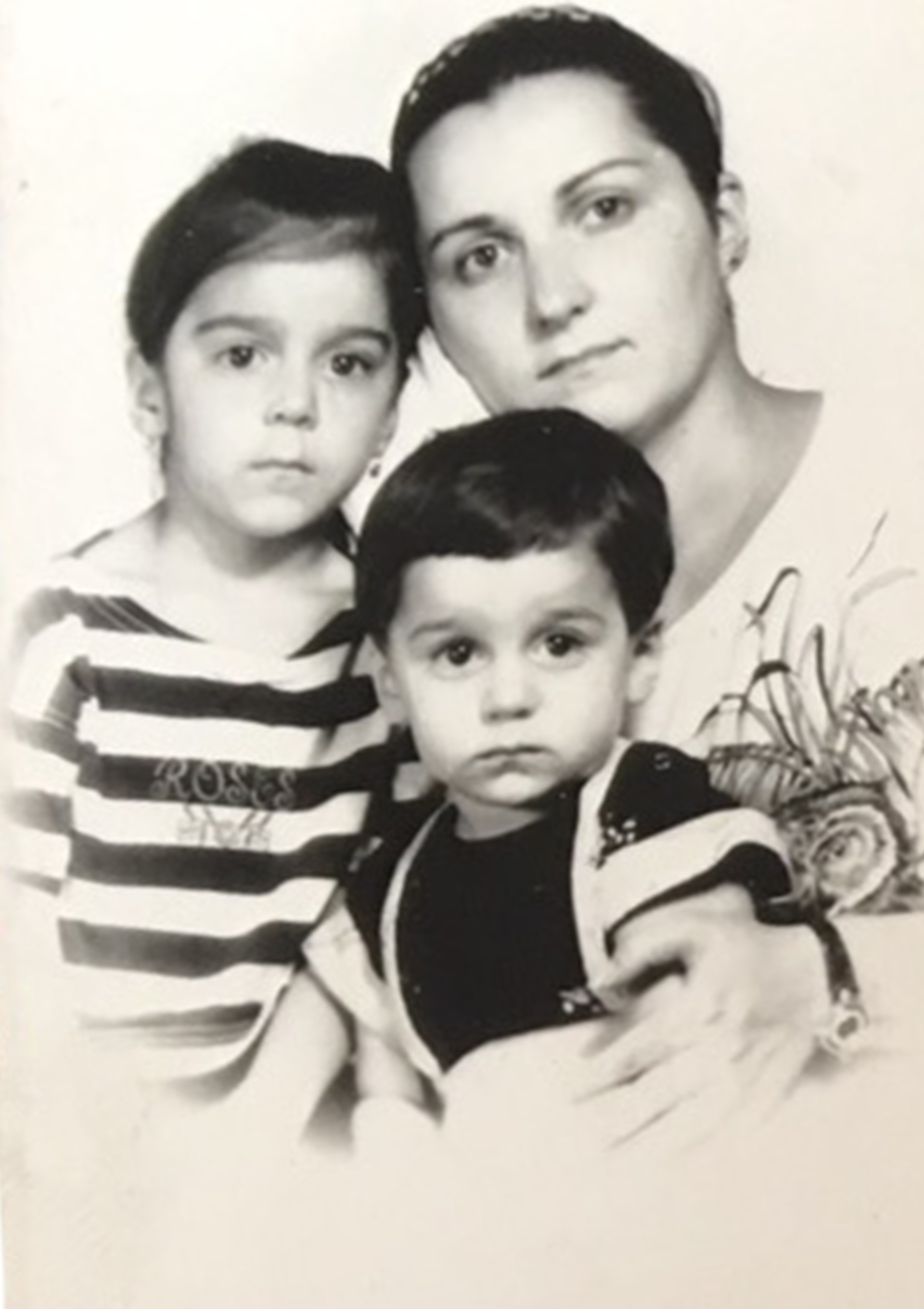

I remember seeing my mother and older sister always crying, and I would ask them, “Where is my father?” No one could explain what was going on.

Day by day, they started to tell to me what had happened.

I remember my mother saying, “Henrikh, he will never be with us.”

And I thought, Never? Never is such a long time when you are seven years old.

We had a lot of videotapes of him playing in France, and I would watch them very often to remember him. Two, three times a week I would watch his matches, and it would give me a lot of happiness, especially when the camera showed him when he was celebrating a goal or hugging his teammates.

On those videotapes, my father lived on.

The year after my father died, I started football training. He was the drive for me, he was my idol. I said to myself, I have to run just like him. I have to shoot just like him.

By the time I was 10 years old, my entire life was football. Training, reading, watching, even playing football on PlayStation. I was totally focused on it. I especially loved the creative players — the maestros. I always wanted to play like Zidane, Kaká and Hamlet. (Pretty good company for my father.)

It was very difficult, because my mother had to be both a mother and a father to me. It’s very hard for a mother to do this in society. She had to stick up for me, and also sometimes be hard with me like a father would be. I had days when I was coming home from training saying, “Ah, it’s so hard. I want to quit.”

And my mother would say, “You don’t quit. You have to keep working, and it will get better tomorrow.”

After my father’s death, my mother had to take a job to support our family. So she started working for the Armenian football federation.

This became quite funny actually once I started playing for the Armenian youth national team. If I would get emotional and act up on the pitch, my mother would come to me after the match and say, “Henrikh! What are you doing? You must behave or I’m going to have trouble at work!”

I’d say, “But mom, they kicked me! They….”

“No, no, no. You must always be polite!”

As tough as it was for us with my father gone, my mother and sister were always pushing me. They even let me go to Brazil by myself when I was 13 to train with São Paulo for four months. That was one of the most interesting times of my life, because I was a very shy kid from Armenia who didn’t speak any Portuguese. But I didn’t care at all because, to me, I was getting to go to football paradise.

I dreamed of being like Kaká, and Brazil was the home of that creative style, which the Brazilians callginga. I actually studied the Portuguese language for two months before I left, but when I arrived in São Paulo I quickly found out that it’s one thing to study, but it’s another thing to speak with the people.

I had gone over with two other Armenian players. When we got to our room, we realized we had a Brazilian player as our roommate. He was kind of skinny like me, and he had dark hair.

He greeted us and said, “Bom dia! Meu nome é Hernanes.”

At the time, this kid was just a stranger, but it was the Hernanes, the one who plays for Juventus now.

We lived at the training ground. We ate there, trained there, had fun there. We didn’t have a PlayStation, only a TV, and everything was in Portuguese. So for the first few weeks, it was very hard because I couldn’t communicate with the Brazilian players. They’d just say something and smile at me, then pat me on the back. The Brazilians are amazing in their nature. You cannot describe it, you must feel that warmth when you’re around them to understand.

Thankfully, everybody spoke the universal language of football. We became friends by communicating through creativity on the pitch. I remember I scored a few goals in training one day, and I thought, “Wow, I am an Armenian kid scoring goals in Brazil.” It made me feel like a star.

After a few months, I could speak basic Portuguese pretty well, and I had taught Hernanes the Armenian alphabet.

I was so interested in the culture. It’s very different. For example, we would train for 45 minutes, then rest for 15 minutes. We would eat some fruits, drink some juice and then go back out and train for another 45 minutes. They train like it’s a real match all the time. In Armenia, at that age, we’d train more physically than technically. In Brazil, it was very technical — always with the ball.

In fact, if the kids don’t have a football, they are playing with a bunch of socks rolled up in a special way to make a ball. Everything is about the ball.

It was funny, because my mom was calling me often — pretty much every day. And I was always telling her that if she wanted to call, she needed to tell me in advance. You see, the only phone we could use for international calls was in the director’s office, so every morning one of the assistants would come running to me on the training ground and say, “Hey, your mom is on the phone.”

Then I’d have to run inside and tell her to call me later.

“How’s my baby? How’s the food? Are you eating O.K.?”

“Mom, I have to train! Call me on Sunday!”

After a few months, I could speak basic Portuguese pretty well, and I had taught Hernanes the Armenian alphabet. Without a PlayStation, there was nothing else to do!

That time was very important to me, because it shaped my style as a player. When I returned to Armenia after four months in Brazil, I was still quite skinny and weak, but I had technique and skill. I was feeling very free on the pitch. I was feeling like the Armenian Ronaldinho. (Hahahaha. No, I’m joking.) It was challenging because I now had three languages in my brain all the time — Armenian, French and Portuguese — and they were competing with each other.

I’d say half a sentence in Armenian and half in Portuguese. (And I am doing this now in English, so please excuse any funny words!)

Then, when I was 20, I moved to Metalurh Donetsk in Ukraine, and I added a bit of Ukrainian and Russian to the mix. It was really funny because two years later when I moved across town to Shakhtar Donetsk, many people said it was going to be very difficult for me. They said I would not be able to succeed there, because there were 12 Brazilian players at the club.

I didn’t say anything, I just laughed to myself. In my mind, I’m thinking, I’m half Brazilian. Of course, I got on great with my teammates, and my three years at Shakhtar were brilliant. I set the record for goals scored in the Ukrainian Premier League in 2013, and it felt good to shut the mouths of those who said I couldn’t make it there as an Armenian.

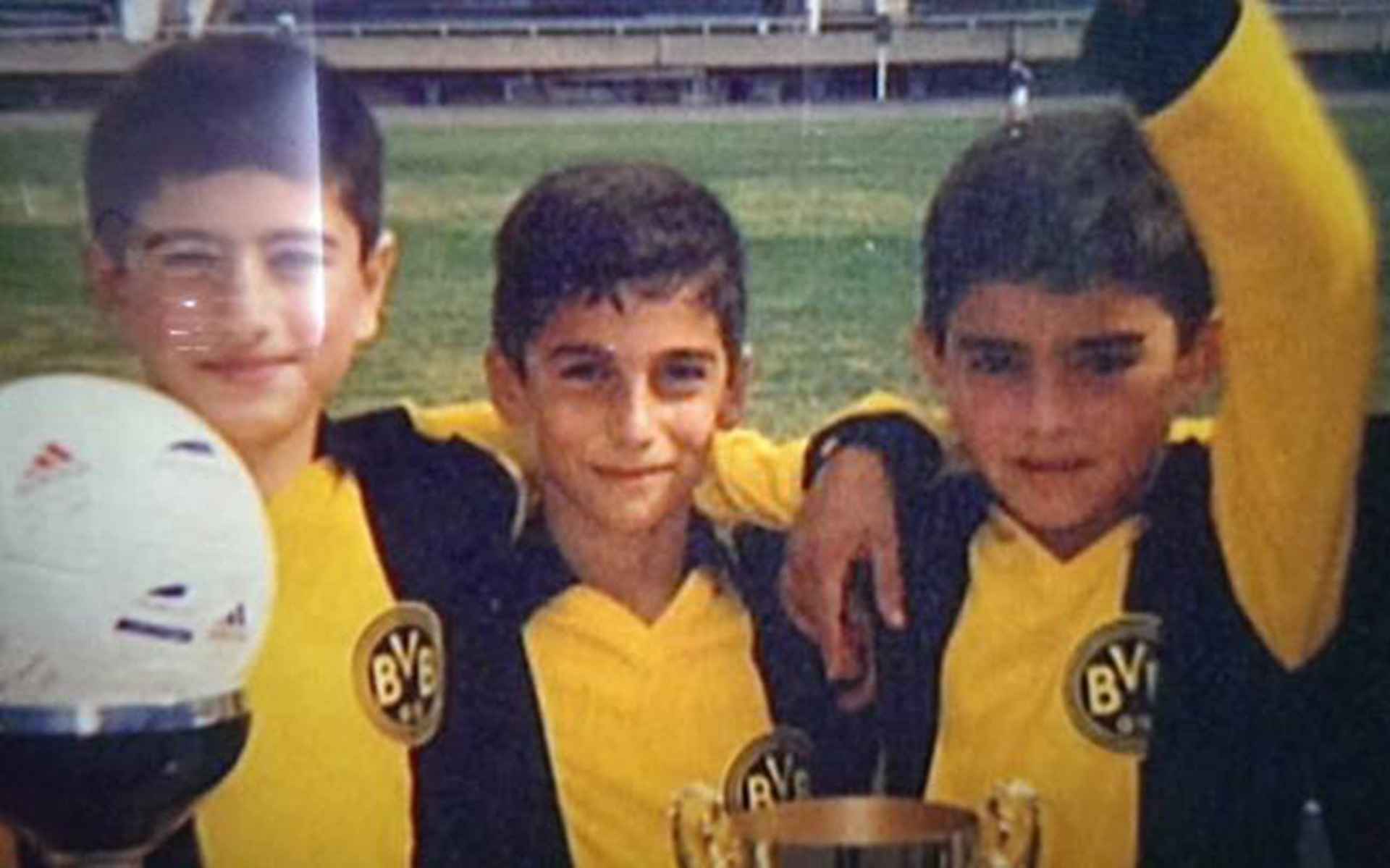

The fate of life can be very interesting. After that season, I was offered a move to Borussia Dortmund, in Germany. Coincidentally, the conflict broke out in Donetsk not long after that, and Shakhtar’s stadium was abandoned.

So I moved to Germany, and not only was it another new language, but also the culture and the atmosphere was very different than what I was used to.

It was a very hard period for me. The first season was O.K., but the second season was a disaster, not only for me, but also for the club. We were losing so much, and I felt like I was having no luck. Not only was I not scoring, but I was not assisting, which is very unlike me. I had been signed for a lot of money, and I put a lot of pressure on myself.

I had many hard nights in my apartment in Dortmund, all alone, just thinking and thinking. I didn’t want to go outside, even to have dinner. But, as I said, fate can be interesting. A new manager, Thomas Tuchel, came to Dortmund before my third season, and he changed everything for me.

He came to me and said, “Listen, I want to get everything out of you.”

I was kind of smiling and laughing, because I thought he was just trying to make me feel better. I was doubting his words.

But he looked at me very seriously, and said, “Micki, you are going to be great.”

That meant everything to me. After the season I had, I didn’t think I could be a star. But he did it. He got everything out of me that season, and it was because I was happy again. When you are sad, you can’t be lucky. This is something I learned from the Brazilian culture. When you are happy, good things happen on the pitch. That season, we played with enthusiasm. We played a crazy, super-attacking style, and we enjoyed every minute on the pitch.

We basically played with two defenders, three midfielders and five strikers, and we had success. Even when we lost, we had fun.

Last summer, my agent called me and said that Manchester United was interested in signing me. It took me by surprise.

I said, “Is it real? Or is it just speculation?”

When your dreams are close to coming true, it does not feel real at first.

A few days later, Manchester United’s interest was confirmed when I got a call from Ed Woodward, their executive director. He told me that the club was indeed interested in me. You can imagine how excited I was by that possibility!

While my agent and the club were negotiating the transfer, I had time to consider my options. I knew it would be a challenge to leave a good situation at Dortmund and succeed at United, but I did not want to sit in my chair as an old man and have any regrets. I was ready to move.

When the deal was done and dusted, I sat down to sign the contract with United and that’s when it hit me … that’s when I realized that this big move to the Premier League was really happening.

I will never forget that moment, nor will I forget the time I put on the red Manchester United shirt before my first training session with the club. It made me feel so happy and proud about what I had achieved in my career.

At the beginning of this season at United, I suffered an injury and have not had many chances to play. It would be fair to say that the start of my life in Manchester was not perfect. But there have been many other times when I’ve had setbacks, and I have never given up. I will continue working every day so that I can help the team succeed.

If you asked my mom and my sisters about me, they would say that I am quite “hard.” I can be very serious. But if I’m being honest, I’m very happy with the way my life has turned out. It was always my dream to play for the biggest clubs in the world.

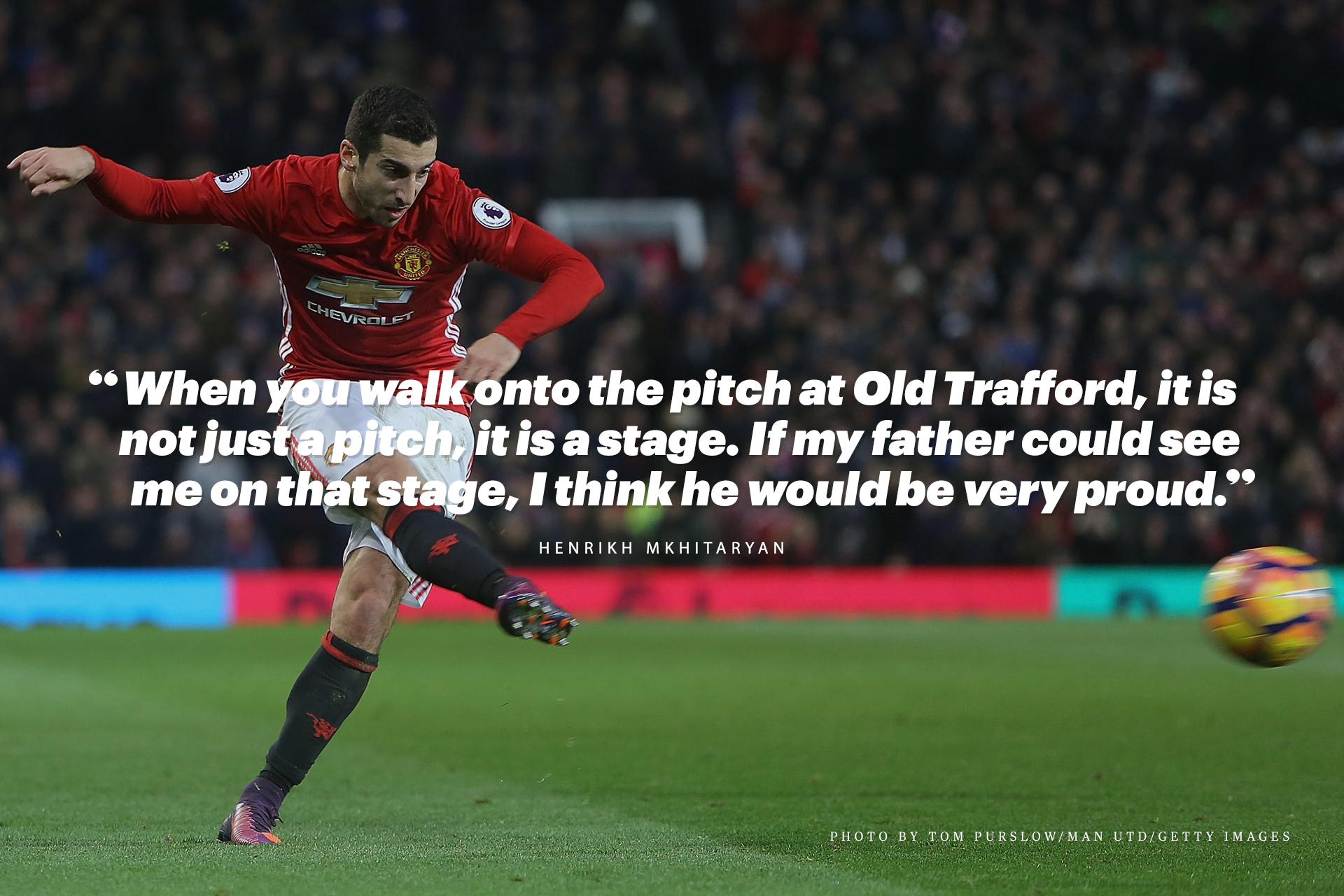

When you walk onto the pitch at Old Trafford, it is not just a pitch, it is a stage. If my father could see me on that stage, I think he would be very proud. I was always kind of chasing him, and I think even though he’s not here, he helped me to get to this place.

If he was still alive, maybe I would be a lawyer or a doctor right now. Instead, I am a footballer.

It’s funny, because after matches I never watch myself on TV. I hate watching myself, because I only notice my mistakes. I am very different from my father in my playing style. He was a fast striker with a powerful shot. I am much more technical. But many people back home in Armenia tell me that I look exactly like my father when I run.

They say, “Henrikh, you look the same, you run the same. You remind me so much of Hamlet when I watch you.”

I wouldn’t know because I can’t stand to watch myself, but it makes sense. I first dreamed of running free on the pitch by watching the videotapes of him after he was gone.